このページを 日本語 で読む

Plastic has become indispensable in modern life. Primarily made from petroleum, it often lingers in the environment long after use. The impact of microplastics and other pollutants has emerged as a major global concern.

In response, a research team led by Takuzo Aida, Group Director at RIKEN and Distinguished Professor at the University of Tokyo, has achieved a groundbreaking development: plastic that dissolves in seawater. This innovative material uses compounds commonly found in food additives.

Their findings, published in Science on November 22, 2024, reveal that this plastic matches the strength and processability of conventional plastics while being eco-friendly. It is expected to serve as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics.

Microplastic Fragments

Around 430 million tons of plastic are produced globally each year, yet less than 10% is recycled. Most discarded plastic is incinerated, releasing carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. Additionally, plastic waste breaks down into microplastics — tiny fragments that threaten ecosystems and human health.

From November 25 to December 1, 2024, the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee of the UN Environment Programme met in Busan, South Korea, to draft the first international treaty addressing plastic pollution. The treaty aims to curb the environmental damage plastic waste inflicts on oceans and ecosystems. It acknowledges that plastic pollution is a crisis comparable to climate change.

The research team developed a material called supramolecular plastic. Supramolecules are assemblies of two or more molecules held together by weak interactions like hydrogen bonds. Their structure allows innovative functions beyond single molecules. The rapidly advancing field of supramolecular chemistry has gained attention for its potential in material development.

Breaks Down in Salt Water

Conventional plastics are made from large polymer molecules formed by bonding smaller units called monomers. When polymers are built from supramolecules, their bonds break more easily, allowing the material to revert to its monomer form. This property has traditionally limited them to soft, rubber-like materials.

The team combined two monomers: sodium hexametaphosphate, used in food additives and fertilizers, and guanidinium sulfate, easily synthesized from natural raw materials.

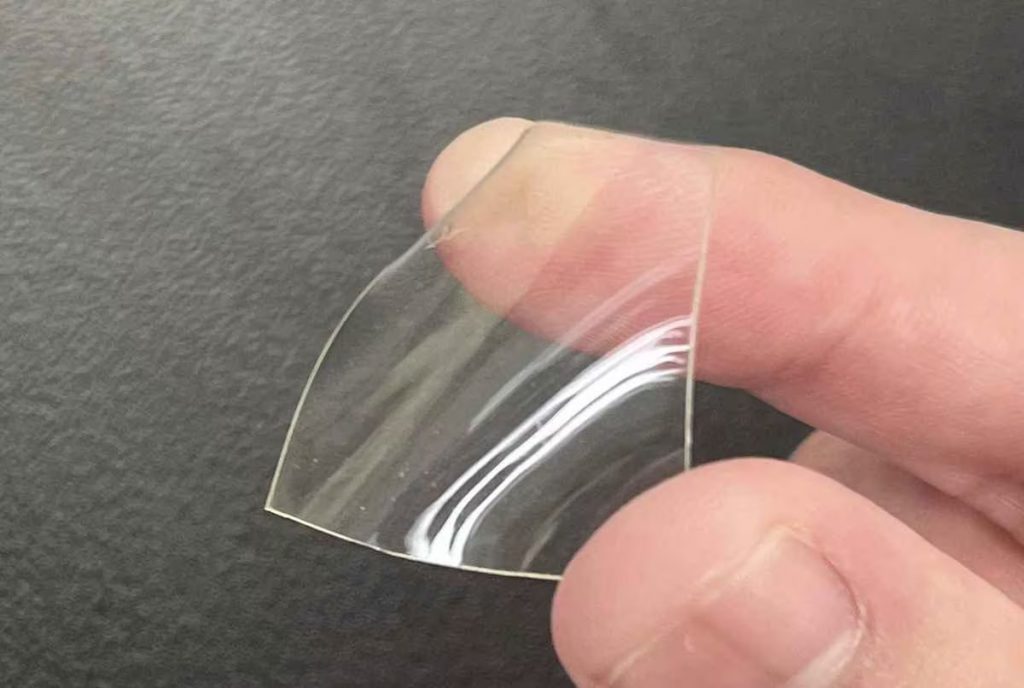

When mixed in water at room temperature, the solution separates into a liquid upper layer and a gel-like lower layer. Drying the gel produces a colorless, transparent, glass-like supramolecular plastic. This simple manufacturing process is well-suited for mass production.

This plastic is flame-retardant and heat-resistant, but when exposed to saltwater, its chemical structure changes. Within half a day, it decomposes into reusable monomers, which bacteria can further break down. Containing nitrogen and phosphorus, these monomers could even serve as fertilizer.

Coating the plastic with a water-repellent film — made from eco-friendly materials — can extend its lifespan in saltwater environments.

Improving Supramolecular Plastics

By modifying the guanidinium sulfate monomer, the team created supramolecular plastics with varied properties, excelling in heat resistance, hardness, or tensile strength. They also replaced sodium hexametaphosphate with sodium chondroitin sulfate, a naturally derived polysaccharide, to produce plastics suitable for 3D printing.

Professor Aida shared that research on monomer combinations for supramolecular plastics began in 2020. Since their Science publication, the team has received a surge of inquiries from both domestic and international sources.

"With the global challenge of plastic waste in mind, we are committed to developing even better supramolecular plastics," Professor Aida said, expressing his enthusiasm for the future of this research.

RELATED:

- Nanoplastics Detected in Human Blood for the First Time in Japan

- Littering in Nara: Plastic Found in Stomachs of Dead Deer

- Japan’s Plastic Recycling: The Unseen Reality

(Read the article in Japanese.)

Author: Shinji Ono, The Sankei Shimbun

このページを 日本語 で読む