Last in a series of 5 articles

Part 1: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: Natural Resources and Root of Manufacturing

Part 2: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: The Power of the Warrior Spirit

Part 3: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: A Test of Character, Past and Present

Part 4: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: Proud Thieves Seeking the Riches of the Sea

The Japanese have been hunting whales since ancient times. It is impossible to consider the relationship between the Japanese people and the sea without examining the history of whaling.

This is the fifth of a series of five articles on “Whales in the Japanese Landscape.” The series is part of a larger ongoing collection published by the Sankei Shimbun in Japanese, titled “Tales of the ‘Watatsumi’” after the Japanese god of the sea.

In this article, we take a look at traditions of respect paid to the life of whales that were caught, and the rites of appreciation that sent the sacrificed giants’ spirits off in peace.

Traditional whaling was a violent struggle between man and whale. At the end of the long battle, the fishermen that had conquered the whale chanted the Buddhist rites and sent its soul to the afterworld.

The whalers lived in a brutal reality, one that took advantage even of the love between a mother whale and its child. Some scholars are even investigating the link between the brightly painted whaling boats of the era and the belief in the Buddhist afterlife.

Penitence

A bridge made of whale bones spans a small lake on the grounds of Zuikoji Temple in Osaka. This is the Setsugei Bridge, which is even depicted in the Settsumeshozue, a famous collection of illustrations from the Edo period.

The bridge was constructed in 1756 from 18 whale bones that were delivered from Taiji.

According to the temple, the chief priest was on a pilgrimage when he visited Taiji, and the locals asked him to pray for a plentiful hunt. He first refused on the grounds that the taking of life was forbidden under Buddhism, but relented when he saw the suffering caused by the recent lack of catches.

He prayed for a successful hunt and the local fishermen were blessed and able to catch a whale. The bridge was built as a memorial.

Successive chief priests of the temple have preserved the bridge and rebuilt it in the years since. The present-day version, constructed in 2019, is the seventh generation. Current Chief Priest Akifumi Toyama says that over the generations, the bridge has “expressed the feeling of living in penitence after breaking a (Buddhist) commandment.”

In the days of traditional whaling, a short moment of silence was held at sea at the instant when an enormous life was taken. In Kyushu, as a roiling whale breathed its final breath and sent up its death cry, the whalers were said to have chanted the “Namu Amida Butsu” Buddhist sutra for the dead three times, and chanted a short Buddhist prayer for right whales.

Stone markers built to memorialize dead whales remain all along the Japanese coast, from Aomori to Aichi to Oita.

Praying They Rest in Peace

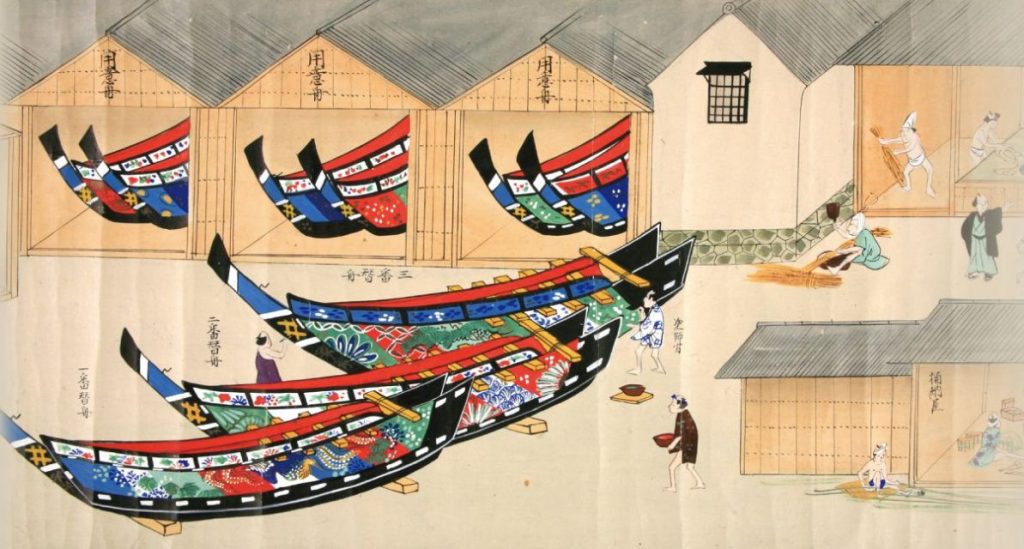

One scholar is investigating a possible religious meaning behind the brightly colored designs on the traditional whaling boats used in Taiji.

The sekobune boats of the fleet, which carried the elite harpooners, were decorated with a variety of motifs. The one that carried the most senior leader was painted with a phoenix in a paulownia tree, while others had chrysanthemum flower crests, the traditional pine-bamboo-plum motif, flowing chrysanthemum patterns, and ivy designs. The variety of the designs have until now been described as a way of differentiating the roles of the various boats. But a purely practical explanation doesn’t account for the intricacy of the designs or the large sums of money it cost to paint them.

Hayato Sakurai, a curator at the Taiji Historical Archives, sees a connection to belief in the Buddhist paradise known as “Fudaraku” in Japanese, a place said to exist far out at sea, where the bodhisattva Kanzeon (also Kannon) resides.

“When the brightly painted boats surrounded a whale, they created a purified world on the ocean. Perhaps in showing the whale this paradise, they prayed that it would pass from this life to the next in peace,” he explained.

Mother and Calf

The Masutomi clan, which managed the whaling operations based on Ikitsuki Island in Nagasaki Prefecture, commissioned an ink painting of a mother right whale and her calf swimming side-by-side. This image was derived from a specialized whaling technique.

The whalers would capture a whale calf, put it into a net, and then attach it to a boat. The mother would not flee, but instead would attempt to free the calf using her tail fluke. This method allowed the whalers to capture both the calf and its mother.

According to Shigeo Nakazono, the curator of Ikitsuki Island Museum Shima no Yakata, “This method takes advantage of the love between a mother and her calf, and can be considered quite cruel. But we should also focus on the fact that it was clearly documented, with no attempt to hide it. Perhaps it was recorded to serve as a reminder of the unavoidable necessity of taking the lives of other living things.”

Tragedy Marks Opening of Modern Era

Near Taiji Harbor, a monument stands in memory of a sea disaster that occurred in December of 1878. It was a great tragedy in which over 100 men died or went missing. They were pursuing a right whale and her calf when they were caught in rough weather, so the incident is known as the “Right Whale Disaster.”

The whaling boats had to abandon their catch, and the fleet was separated and drifted over a wide area. Some washed up on Kozushima Island on Ito Peninsula, over 300 kilometers away. Gorosaku Taiji, who was a child when the accident occurred, recalled years later that when the men went missing, “many women, who appeared to be their wives and daughters, wandered aimlessly around the town for days, weeping and crying out in loud voices.”

Traditional whaling had been practiced in Taiji since the early days of the Edo period, but the disaster was a devastating blow from which the old style of whaling would never recover.

This marked the beginning of the modern whaling era, which would employ boats with engines, and harpoons fired from cannons.

Over 140 years later, I spoke with Takashi Takeuchi, the captain of the Katsumaru No. 7, a modern whaling boat that operates out of Taiji.

“When we catch a whale, we cut off the tip of the tail and offer it to the ‘Funagamisama’ (the Shinto deity that protects the boat),” Captain Takeuchi explained. “We give thanks that we were able to make the catch without incident. We can’t forget our gratitude for the gift of another life.”

The methods and equipment may change, but the spirit of gratitude toward nature does not. His words echoed pleasantly in my ears.

A Heavy Responsibility Toward the Future

My investigations around whales and whaling have taken me beyond the spirituality of the Japanese, to something more universal.

In part four of this series, I came across the practice of kandara. There was a time when people began to draw lines across nature, divvying up and claiming natural resources that had previously belonged to no one. The sense of guilt the whaling families felt at their monopoly compelled them to overlook the small-time thieves that preyed on their catch, a fascinating detail.

In 2019, Japan withdrew from the International Whaling Commission and restarted commercial whaling. This can be considered an objection to the international monopolization of whales as something to be protected at all costs.

Japan opted to bear the responsibility of sustaining this natural resource under its own criteria. The country bears a heavy responsibility in connecting its whaling history, which spans 6,000 years, to the future. We must continue to feel gratitude toward the blessings of nature.

(Read the column in Japanese at this link. This article is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.)

End of series

Author: Hideaki Sakamoto