Do Newly Discovered Bacteria Hold the Key to Curbing Methane Emissions?

Japan is working to reduce emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas methane using newly discovered bacteria believed to help reduce the gas in cow burps.

このページを 日本語 で読む

Methane emissions from cow burps are one cause of global warming. As countermeasures have become a worldwide issue, Japan is advancing its own research as a national project, and its focus is bacteria.

The plan is to reduce methane emissions by feeding cows a newly discovered type of bacteria. The bacteria are expected to work in the same way bacteria from yogurt balance bacteria in human intestines. Details of the government's strategy follow.

Burps Total 5% of Global GHGs

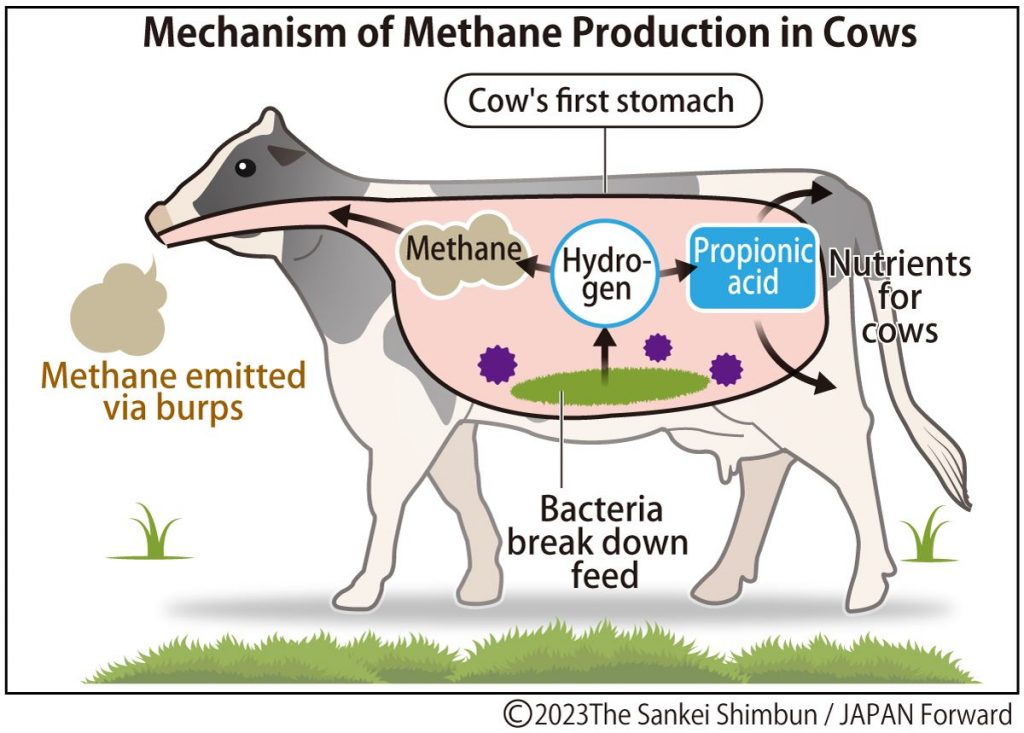

Cows obtain nutrients by fermenting grass or grains in their stomachs. Methane is produced during this process. It is released in burps roughly once every one to two minutes as the stomach moves.

According to the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), beef cattle emit approximately 250 liters of methane per day on average, while dairy cows can emit as much as 500 to 600 liters per day per animal.

Methane, a greenhouse gas, is a substance formed by carbon and hydrogen. Its greenhouse effect is tens times greater than CO2, and its impact on global warming is second only to CO2. It is generated from rice paddy farming, livestock farming, and fossil fuels. Methane's concentration in the atmosphere has continued to rise.

Among these various sources, methane from the burps of ruminant livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep accounts for a whopping 5% of total greenhouse gas emissions worldwide (converted to CO2 equivalent).

As the world’s population increases and the demand for meat rises, reducing methane emissions from livestock burps has become a major international challenge.

As a side note, methane is not present in human burps due to the highly acidic environment of the stomach, which generally prevents the growth of bacteria.

Methane-Generating Archaea

So, how is methane generated in cows?

A cow's stomach has four compartments. Multitudes of microorganisms live in the first two compartments. These include not only bacteria but also archaea, which are similar but different from bacteria.

Cows use the activity of these archaea to break down their food and convert it into organic matter, which serves as a source of nutrients and energy.

The many archaea in a cow's stomach have the ability to produce methane. They are the cause of methane emissions.

When organic matter, which serves as a source of nutrients, is produced in the stomach, hydrogen is generated as a byproduct. Hydrogen, which inhibits the growth of most bacteria, is a problem for cows. But for the archaea that produce methane, this hydrogen is the raw material.

This mechanism of methane production may be problematic for the global environment. But, it is beneficial for cows as it reduces the amount of unnecessary hydrogen.

Like Feeding Cows Yogurt

So how can methane emissions from cow burps be reduced?

Around the world, the development of substances that suppress the activity of methane-producing archaea has become a mainstream approach. These substances can be mixed into the animals' feed.

In Europe, for example, a synthetic substance called 3-Nitrooxypropanol, or 3-NOP, has been approved as a feed additive. It is believed to reduce methane emissions by 30%.

Research is underway in Australia on the efficacy of a component of a seaweed called Asparagopsis (Asparagopsis taxiformis) that has been shown to be effective in reducing methane emissions.

Meanwhile, NARO has its own unique strategy for reducing methane emissions. It aims to feed cows a certain type of bacteria. The concept is similar to people eating yogurt rich in probiotics. Here's how it works.

The bacteria in a cow’s stomach break down its food to produce substances that serve as nutrients. Most bacteria primarily produce acetic acid. Hydrogen, the raw material for methane, is generated in the process.

However, there are certain bacteria that produce a different type of nutrient called propionic acid. In this process, hydrogen is consumed as a raw material, leading to a decrease in the amount of hydrogen available.

There are thousands of known bacteria living in cow stomachs. In 2021, NARO was the first in the world to discover a new bacterium. Compared to other bacteria, it produces more of the substance that serves as a raw material for propionic acid.

Cows carrying this new type of bacteria have been found to emit 10-20% less methane. The bacteria are believed to be using hydrogen to produce propionic acid instead of methane. NARO expects that by adding this bacteria to cattle feed, methane emissions can be reduced.

Multiple Benefits of Bacteria

From the perspective of the livestock industry, methane production means that a portion of the energy from the feed is lost as a gas. It ends up wasted.

The newly discovered bacteria produces a large amount of the raw material for propionic acid. This not only helps reduce methane emissions but also increases nutrients for cattle.

Thus the bacteria are promising both for combating global warming and increasing feed production.

Itoko Nonaka, a research group leader at NARO, says, "Unlike synthetic substances approved in Europe, the use of microbes naturally present in cattle could be less objectionable to consumers."

Currently, NARO is conducting foundational experiments to determine the function of this bacteria. Going forward, the bacteria will be administered to actual cattle to determine the extent of its methane reduction effect.

Aside from determining efficacy, cost will be a challenge for a product to be commercialized.

The research has been selected by the Moonshot Research and Development Program, which involves large investments by the government in innovative research projects.

Working hand in hand with other research teams, such as one from Hokkaido University, the team aims to reduce Japan’s domestic cattle methane emissions in 2050 by 80% compared to 2013 levels. Research also aims to increase milk production by 10%.

"Cows have lived with humans and supplied us with food for about 9,000 years. As the global population increases, continued co-existence with cows will ensure a stable supply of high-quality protein," emphasizes Osamu Sasaki, research manager at NARO.

"Our research aims to find a balance between methane emissions reduction and livestock production," he adds.

このページを 日本語 で読む