The Incredible Survival Skills of the Japanese Eel

Researchers have recently discovered that juvenile eels increase their chances of survival by using tricky maneuvers to escape from a predator's body after being swallowed.

このページを 日本語 で読む

The Japanese eel is a well-known ingredient in Japanese cuisine. However, wild populations are shrinking, raising concerns about potential extinction and rising prices. Overfishing and environmental damage are major causes, while predatory fish also pose a threat to young eels during their growth stages. However, researchers at Nagasaki University have discovered an extraordinary survival skill in juvenile eels that enables them to escape from predators even after being swallowed. So, how do they accomplish this remarkable feat?

Decline of Wild Eel Populations

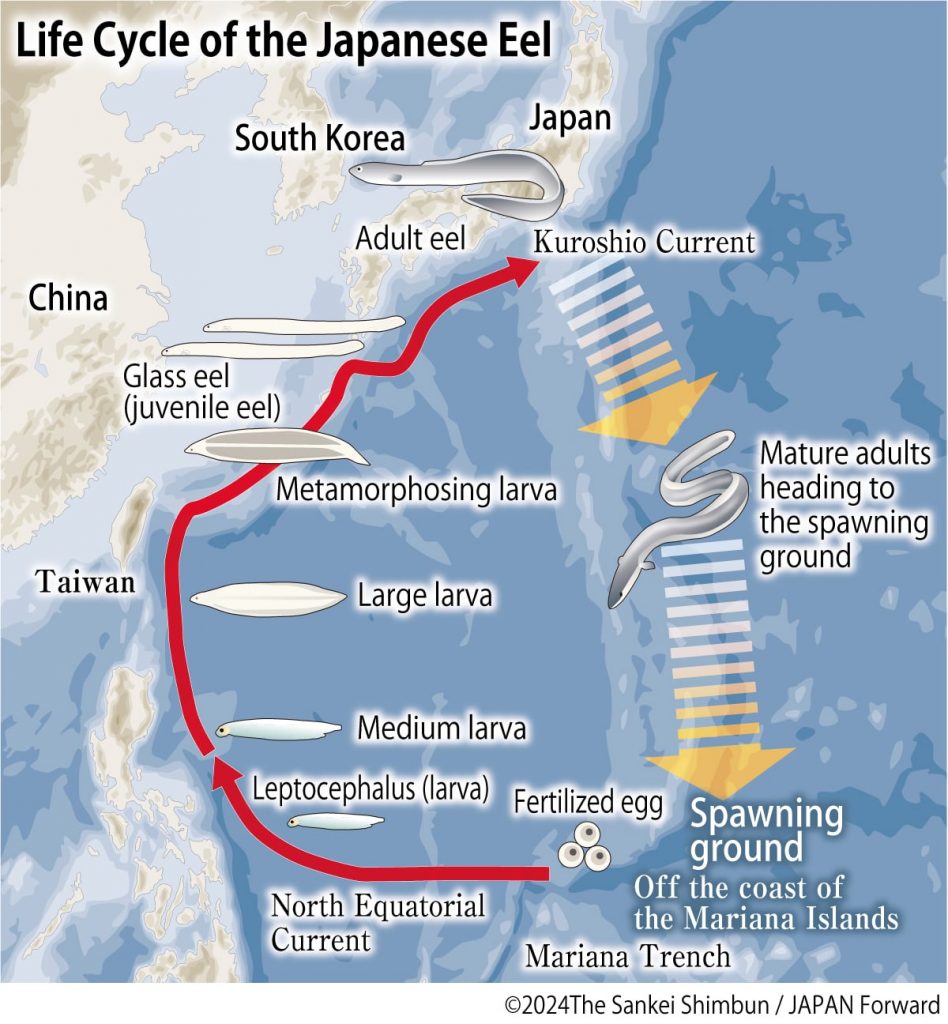

The Japanese eel inhabits rivers and estuaries, spending 5 to 15 years maturing before migrating to spawn near the Mariana Trench, about 2,000 kilometers south in the Pacific.

After hatching, the larvae — known as leptocephalus and shaped like willow leaves — travel westward on the North Equatorial Current, reaching waters near the Philippines and Taiwan.

From there, they ride the Kuroshio Current northward, transforming into juvenile glass eels, or "shirasu-unagi," and returning to local shores. Glass eels caught at river mouths are raised in captivity, eventually becoming the farmed eels sold in stores.

In Japan, annual glass eel catches exceeded 200 metric tons in the 1950s but have since dwindled to around 5 tons. This scarcity has driven up prices, with a single grilled farmed eel now costing nearly ¥3,000 JPY (about $20 USD) in supermarkets.

The drop in numbers is partly due to a decline in wild eels, which are highly prized, sometimes fetching several times the price of farmed eels. Overfishing and degraded river habitats also play a role.

Another lesser-known factor is that eels often fall victim to predatory fish after reaching rivers. These combined pressures have reduced the number of eels migrating south to spawn, which in turn has lowered the number of glass eels returning to Japanese coasts.

The Great Escape

Researchers from Nagasaki University set out to uncover the defensive strategies of juvenile eels. The team investigated how these young eels responded when confronted with the dark sleeper, a predatory freshwater goby that can grow up to 25 centimeters in length.

To study this, they placed juvenile eels, measuring 6 to 7 centimeters long and still darkly pigmented, into tanks containing a dark sleeper and filmed the encounters.

Initially, the footage showed juvenile eels either being devoured whole or successfully dodging attacks. However, one day, Assistant Professor Yuha Hasegawa (then a college senior) noticed an eel swimming in the tank after it had been swallowed.

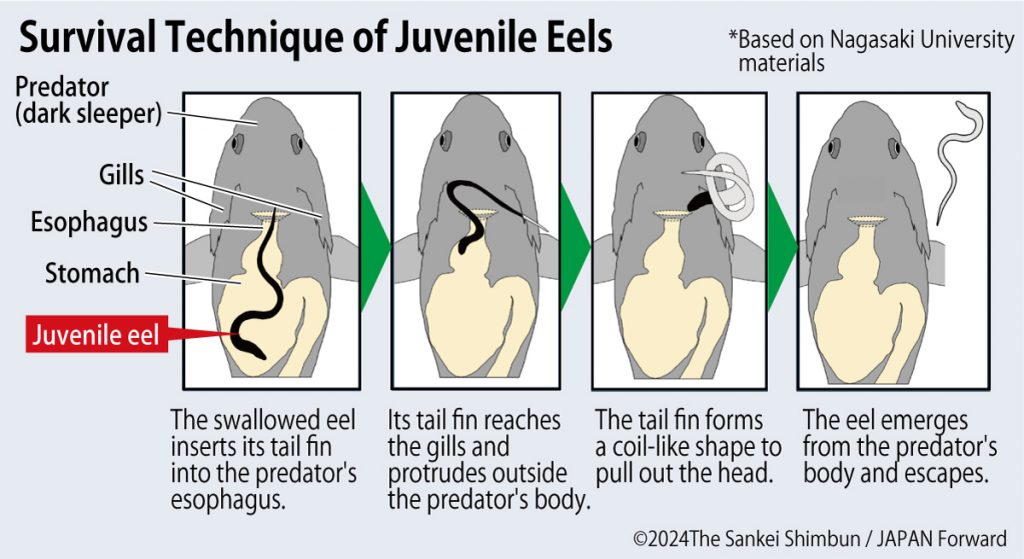

Curious about this observation, Hasegawa set up a long-duration camera to monitor the tank. The results revealed that out of 54 swallowed eels, 28 managed to escape through the gills of the dark sleeper.

Remarkably, the fastest escape took just six seconds, while even the slowest eels exited in just over two minutes, and all of them emerged tail-first.

A Second Chance at Life

To understand this escape tactic, the team injected a contrast agent into the juvenile eels and fed them to the dark sleeper. Their escapes were then filmed with an X-ray video camera.

Surprisingly, the eels did not escape immediately through the gills near the mouth. Instead, they moved through the digestive tract, with some rotating their bodies as if probing with their tails to find an exit.

Those who managed to find their way back up the esophagus maneuvered their tails outside the gills and twisted their bodies in a loop. Using their tails for leverage, they pulled themselves free from the digestive tract.

Eels that failed to escape became motionless within an average of 3 minutes and 20 seconds, likely due to the strong stomach acids and low-oxygen environment.

While it's not unusual for fish with spikes or other physical defenses to be spat out after being swallowed, active escapes from a predator's digestive tract are quite rare. Japanese eels appear to leverage their slender, slippery bodies and ability to swim backward to their advantage.

Professor Yuuki Kawabata, who led the study, explained, "Japanese eels are currently being released nationwide to aid in population recovery. Understanding their interactions with predators could help us select the most suitable release sites. We plan to conduct further research on the eels' escape behavior."

RELATED:

- 'Sea Hammocks' Made from Recycled Fishing Nets Spotlight Marine Plastic Waste Issue Ahead of Expo

- Washoku: Can Japanese Cuisine Be Made Even Healthier for Future Generations?

- Mudskippers Jumping for Love in Kyushu's Ariake Sea

- 'Super-Invasive' Fish: Environmental DNA Study Reveals Ecosystem Threat

Author: Juichiro Ito, The Sankei Shimbun

このページを 日本語 で読む