Dryland Fish Farming: From Beloved Salmon to Filefish

With the impact of climate change on fisheries and a rising world population, investors from overseas are showing growing interest in Japan’s fish farming industry.

このページを 日本語 で読む

The dryland fish farming business, which aims to grow fish and shellfish through land-based ponds on dryland farms in Japan, is showing signs of speeding up. Firms from other fields are entering the business, and fish farming ventures are making an appearance.

These companies are making active attempts to switch from a fish-importing model to a domestic based supply, and to add additional value to Japanese-raised fish.

Government efforts to restore self-sufficiency in seafood production, however, are only halfway to their goal. Authorities need to speed up the creation of a framework for supporting these businesses.

The fish farming business has grown while capitalizing on each region’s natural environment. There are marine water tuna, oysters, and seaweed farms, while eels and carp are being farmed in freshwater bodies such as lakes and rivers. The business has now become a pillar of the fishing industry.

On the other hand, the Fisheries Agency does not have a clear definition of dryland fish farming. A representative told us that the Agency understands it is “the practice of farming seafood in a dryland sea water facility, as opposed to freshwater aquaculture.”

In the Aquaculture Growth Industrialization Comprehensive Strategy, released in July 2020, dryland fish farming is described as a business whose technological development is progressing. The strategy recognizes that it requires further surveying in order to come up with dedicated policies. At the moment, the Agency does not have a grasp of how many companies are involved in this business.

A Strategy for Revitalization

JR West is known as a trailblazer company that entered this business early on. It first set its eyes on dryland fish farming in 2013. The project's aim is to promote the locations that are serviced by the company's railway network by boosting local industries and revitalizing those regions.

In 2018, the railway set up its own dryland fish farming brand, PROFISH. An abbreviation for Premium Organic Fish, the new company started offering products such as chub mackerel meant for raw consumption as sashimi. By the end of 2021, it started farming its eighth type of fish — filefish. Even now it is continuing to create farming locations in cooperation with local companies.

In December 2021, Nikken Lease Kogyo introduced Miho Salmon, the trout salmon that it farms at its own facility in Shizuoka City. It uses a 30-meter deep well that's been dug into the ground to reach a layer naturally infiltrated by seawater from Suruga Bay. There, fry, or young fish, grow as much as two kilograms in size within the span of six to eight months.

“We can only produce about 20 tons of fish per year, so it has a high price point,” said a Nikken Lease representative. “We are cooperating with Shizuoka City, its Chamber of Commerce, local distribution, and dining establishments so that it becomes a high-quality brand that makes people want to visit Shizuoka.”

Focused on Salmon Farming

Closed-loop filtration systems have become the standard technology used in dryland fish farming as they have a lower impact on water resources. The systems control the water used for aquaculture by constantly filtering and recirculating it. Water temperature, quality, and food are carefully managed to reduce the risk of allergies and parasites unique to fish. Moreover, the changes in seasons do not affect fish quality.

FRD Japan, Co., based in Iwatsuki-ku, Saitama Prefecture, is a venture company that aims to commercialize dryland farmed fish. It produces 30 tons of trout salmon per year in its experimental facility in Chiba Prefecture, and will start building a facility with a 2,000-ton production capacity by March 2023, in a move toward commercialization.

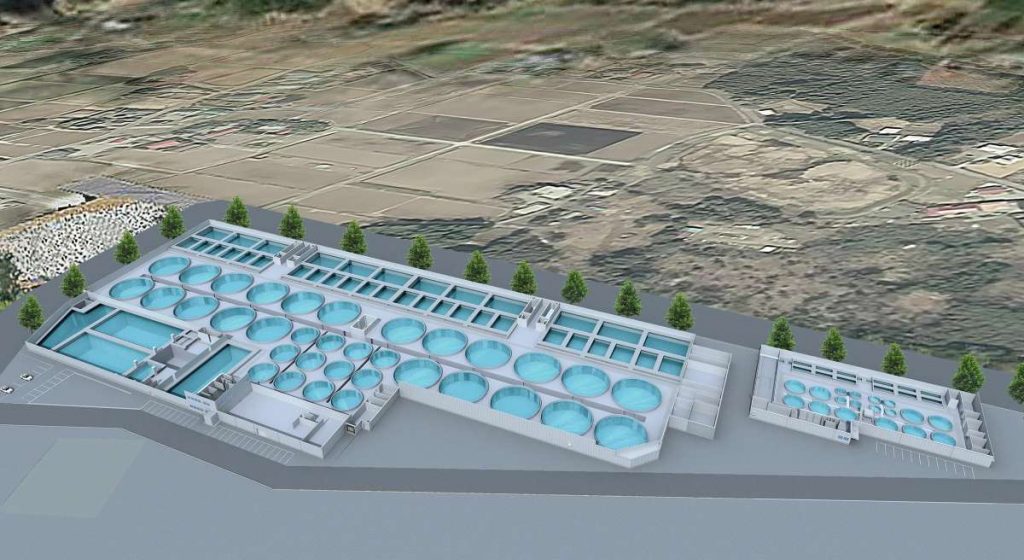

There are also foreign venture companies whose target is large-scale domestic production of Atlantic salmon, an imported fish popular for use in sushi and sashimi. Norwegian firm Proximar Seafood started building a plant in the industrial complex in Oyama, Shizuoka Prefecture last year. With a 28-square-kilometer surface area and a capacity for 6,300 tons of annual production, the total amount of investment is expected to reach ¥17 billion JPY (about $140 million USD).

The egg-hatching facility will be completed by the summer of 2022. The fry will be grown into five-kilogram fish, and the company is aiming to start shipping its product by the summer of 2024. A representative from the Japanese office told us that the reason for entering the market is that, “There is a market for the consumption of raw Atlantic salmon in Japan, and the political situation is stable.”

Another foreign player is the Japanese subsidiary of United Arab Emirates-based company Pure Salmon. The Japanese subsidiary, called Soul of Japan Inc. (Minato-Ku, Tokyo), plans to build a fish farming facility that can produce 10,000 tons of fish per year, along with a processing plant. The project aims to start shipping in fall 2025. The CEO of Soul of Japan, Mr. Erol Emed, explains, “Our facility integrates the primary and secondary industries.”

Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. has started selling insurance aimed at dryland aquaculture companies from January of 2022. It provides insurance against damage to property (i.e., the farmed fish) caused by unexpected accidents. Tokio Marine Nichido says it has already received several requests for quotes.

Elsewhere, the Japanese fishery giant Nippon Suisan Kaisha Ltd. has been conducting experimental dryland farming of chub mackerel and whiteleg shrimp for several years. It is still keeping a cautious stance in order to ascertain the costs related to the initial facility costs, power used while fish farming, and overall business profitability.

Toward a Large-Scale Business Model

Japan’s self-sufficiency rate in edible fish peaked at 113% in 1964 and has been declining ever since. In 2020, it was approximately 57%, two percentage points up from the previous year. But overall both production and consumption have declined.

The next Basic Plan for Fisheries, which the Fisheries Agency of Japan is currently outlining, is expected to target a self-sufficiency rate in edible fish of 94% by 2032. Expansion of domestic production of salmon, a fish which currently has a high import ratio, is expected to be included, along with a reporting system that allows the agency to grasp the real time status of the dryland fish farming industry.

Meanwhile, the global demand for seafood continues to rise. For example, there has been a surge in inquiries related to fish surimi. And eating seafood is often considered part of a healthy lifestyle.

Looking Into the Future of Fish Farming

As Mr. Yasufumi Miwa, an expert from the Center for the Strategy of Emergence of The Japan Research Institute, says, “Right now, dryland fish farming is moving toward a large-scale business model, and it has started to blossom based on its role as an industry that provides a source of animal protein.”

Dryland fish farming is also part of the food processing industry. And companies investing in it say that it is difficult to achieve profitability without moving to a mass production, large-scale industry in which initial investments are lowered.

Considering the impact of climate change on the availability of fish species and quantities, as well as the increase in demand due to a rising world population, Mr. Miwa says, “From a food security point of view, it is crucial to establish another pillar to secure a stable supply of marine products.”

Author: Yukako Hino

このページを 日本語 で読む