Scientists Pinpoint Subsurface Ice on Mars with Unprecedented Accuracy

A Japan-based team has identified abundant subsurface ice on Mars, uncovering prime landing sites that could potentially provide water for future missions.

このページを 日本語 で読む

Vast amounts of ice are believed to lie beneath the surface of Mars. Their exact locations had long remained a mystery — until now. For the first time, a team from Kochi University and other institutions has successfully pinpointed areas with abundant subsurface ice with remarkable precision.

This ice could become a critical resource for future crewed missions to Mars, providing both drinking water and a key component for fuel production. As such, these regions are seen as prime candidates for landing sites. The discovery is expected to significantly influence Mars exploration plans worldwide.

Ice Found at the Bottom of Craters

Based on Mars' surface features and mineral distributions, scientists believe that roughly four billion years ago, an ocean covered much of the northern hemisphere. In contrast, the southern hemisphere is thought to have been dominated by mountains and highlands.

Today, however, Mars is a frozen, barren planet. Although snow occasionally falls in winter, liquid water no longer exists on the surface, which now resembles a vast red desert.

Yet, some of that ancient seawater is thought to remain underground, trapped as permafrost just tens of centimeters to a few meters beneath the surface. Satellite observations have even confirmed ice exposed at the bottoms of craters formed by meteorite impacts and other events.

The Artemis Program, led by the United States, ultimately aims to send a crewed mission to Mars in the 2040s. In the long term, the plan envisions building a permanent human base that utilizes local resources. Mars could also serve as a strategic outpost for missions to more distant worlds.

Establishing a base in an ice-rich area would make it easier to secure water and produce rocket fuel by splitting ice into hydrogen and oxygen. Although crews could search for ice after arrival, identifying its location in advance is essential for efficient mission planning.

Landforms Shaped by Ice

With that goal in mind, the research team sought areas where underground ice is abundant. They focused on the northern hemisphere, where lowlands and snowfall are common. Their search concentrated on latitudes between 30 and 42 degrees north. This is the southernmost range where subsurface ice has been observed at crater bottoms.

Because future missions will rely on solar power, the team prioritized lower latitudes that receive more sunlight and offer safer landing sites.

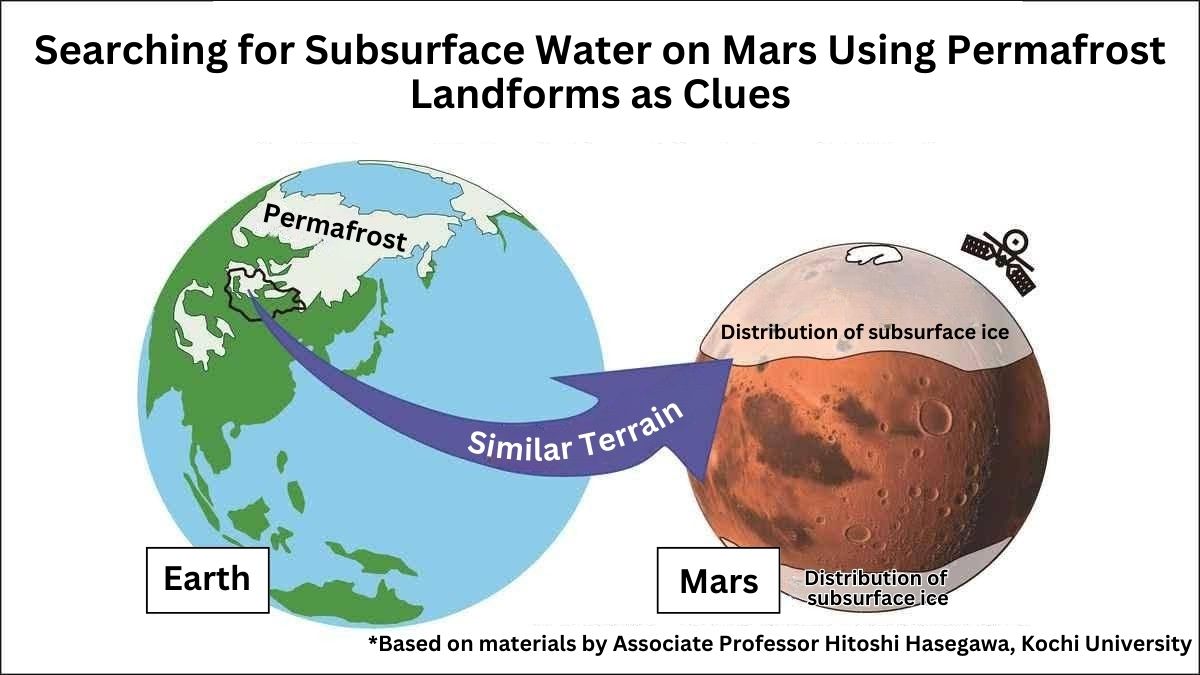

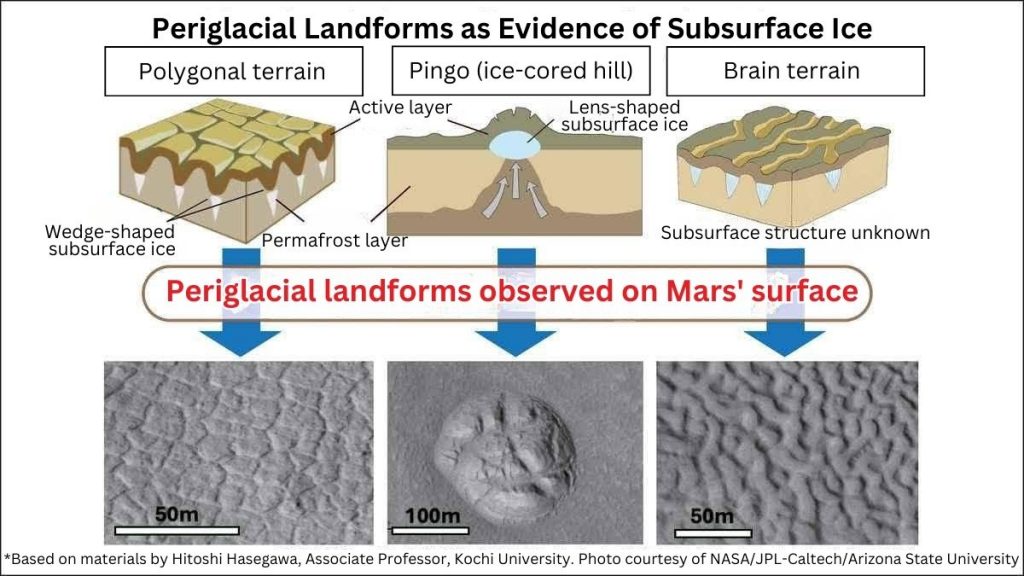

To locate underground ice, they analyzed about 5,000 high-resolution surface images taken by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. They looked for periglacial landforms, distinctive features that indicate the presence of subsurface ice.

On Earth, such landforms are found in permafrost regions like Alaska, Canada, Russia, and northern Mongolia. Formed when water near glaciers freezes and thaws repeatedly, they reshape the surface over time.

There are three main types: polygon terrain, marked by 10–20-meter-wide polygonal patterns, pingos, mounds pushed up by lens-shaped ice, and brain terrain, which resembles the folds of a brain.

Amazonis Planitia

The analysis revealed that all three types of periglacial landforms are concentrated around 40 degrees north latitude. These features are densely clustered in three key regions: Arabia Terra (0–60 degrees east longitude), Utopia Planitia (80–125 degrees east), and Amazonis Planitia (160–210 degrees east). Notably, their distribution closely aligns with areas where ice has been observed exposed at crater bottoms.

The research team concluded that all three regions are rich in underground ice and recommended them as strong candidates for future crewed landing sites.

Among them, Amazonis Planitia stands out as especially promising. It not only contains numerous exposed ice sites at crater bottoms but also displays ice-related surface features spread widely across the plain.

Meanwhile, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) is preparing for an international Mars exploration mission, the Mars Ice Mapper (MIM) project. As part of this initiative, an uncrewed probe is scheduled to land on Mars in the early 2030s.

Associate Professor Hitoshi Hasegawa of Kochi University, a planetary geologist who led the recent study on Martian subsurface ice, is also involved in the MIM mission. "We hope to use this data as an important reference when selecting landing sites for JAXA's uncrewed probe," he said.

RELATED:

- Hayabusa2 Asteroid Samples Offer Clues to the Origins of Life

- DASSAI Sake Takes on the World's First Space Brewing Challenge

- Maido-2: Osaka's Lunar Robot Hopes to Leap into the Future

- Jupiter Moon Io: 20 Years of Research

(Read the article in Japanese.)

Author: Juichiro Ito, The Sankei Shimbun

このページを 日本語 で読む