In October 2022, the 68th meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was held in Portorož, Slovenia. IWC68 was also the first meeting in which Japan, which withdrew from the IWC in 2019, participated as an observer.

This first session in four years brought attention to the IWC’s changing priorities, including several points of significance that deserve discussion. These are examined in a four part series, finishing below with this last part.

Part 1: IWC68: Reflections on the Future of the International Whaling Commission

Part 2: IWC68: An International Whaling Commission in Crisis

Part 3: IWC68: New Contested Issues Emerging from the South

Part 4 of 4

IWC68 ー Non-Western Countries Raise Their Voices

Non-Western and developing countries that are members of the IWC are fighting in the arena prepared and controlled by the advanced Western countries.

This conceptual structure may be behind the fundamental differences evident in the two sides’ ideas and positions on whales and whaling. They could also be the basis for the sometimes emotional confrontation over whaling activities.

There is a reason why developing countries that are not conducting whaling activities support the sustainable use of whales as a living marine resource in the IWC. This may be due in part to their opposition to the standards of advanced Western parties. And their resistance to the countries that impose those rules.

Similar examples are too numerous to mention in recent years. In conventional discussions of international issues, it has been standard practice for advanced Western countries to propose measures and projects. These are then regarded as the global standard.

In developing countries that have difficulty in implementing these measures and projects, the need for capacity building is documented.

For many years non-Western members of the IWC, such as Asian countries, have accepted the global standard. Also, they have worked to implement it, even if they may feel uncomfortable with it. In recent years, however, the pattern might have begun changing.

‘The Future We Want’

An example is the discussion surrounding The Future We Want. This is the outcome document of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) held in Brazil in 2012.

The adopted document defined the concept of a green economy. However, developing countries expressed strong opposition to this concept during the Conference.

They argued that it was the Western industrialized countries that have been destroying the global environment. And they said it was selfish for the West to ask other countries to abandon the existing structures and patterns of economic development and shift to a green economy that the West perceived as environmentally friendly.

Moreover, there was opposition to the idea of forcing other countries to accept the new green economy as a global standard. This viewpoint of developing countries has since been reinforced.

Developing Objections at Rio+20 Visible at IWC68

A noteworthy situation also occurred at Rio+20 in the discussions surrounding the oceans.

The Future We Want includes provisions on international instruments that are normative on maritime issues. Among these are the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the UN Fish Stocks Agreement.

Provisions on these widely accepted normative instruments have been adopted without significant conflict or debate in the past. Mostly, the standard language has been a recognition that these documents are international norms and a call for those countries that have not yet acceded to or ratified them to do so as soon as possible.

At Rio+20, however, countries, especially developing countries, expressed their objections to that approach. It was the author’s understanding that their objections, too, may have been caused by an underlying opposition to the legal and conceptual norms that have been formulated by the Western industrialized countries.

Consequently, The Future We Want provisions on these normative documents were modified to allow their adoption. As adopted, their content provides that countries which have already acceded to or ratified the norms should work to realize them. This is just common sense that does not need to be stated as a provision of an important international document.

Emerging Differences at COP, CITES and Beyond

Commonalities may be seen in the debate over the Loss and Damage Fund at COP27 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Similarly, the same concerns are reflected in the opposition from developing countries at CITES COP19, and the discussions at IWC67 or IWC68.

At the same time, developments in discussions in other international organizations are at a level that cannot be ignored. And the destabilization of the world situation caused by the Ukraine conflict, COVID19, and other events is adding further energy to this development.

This resistance to previously assumed norms is a situation that should be closely watched.

New IWC Chair, New Directions After IWC68?

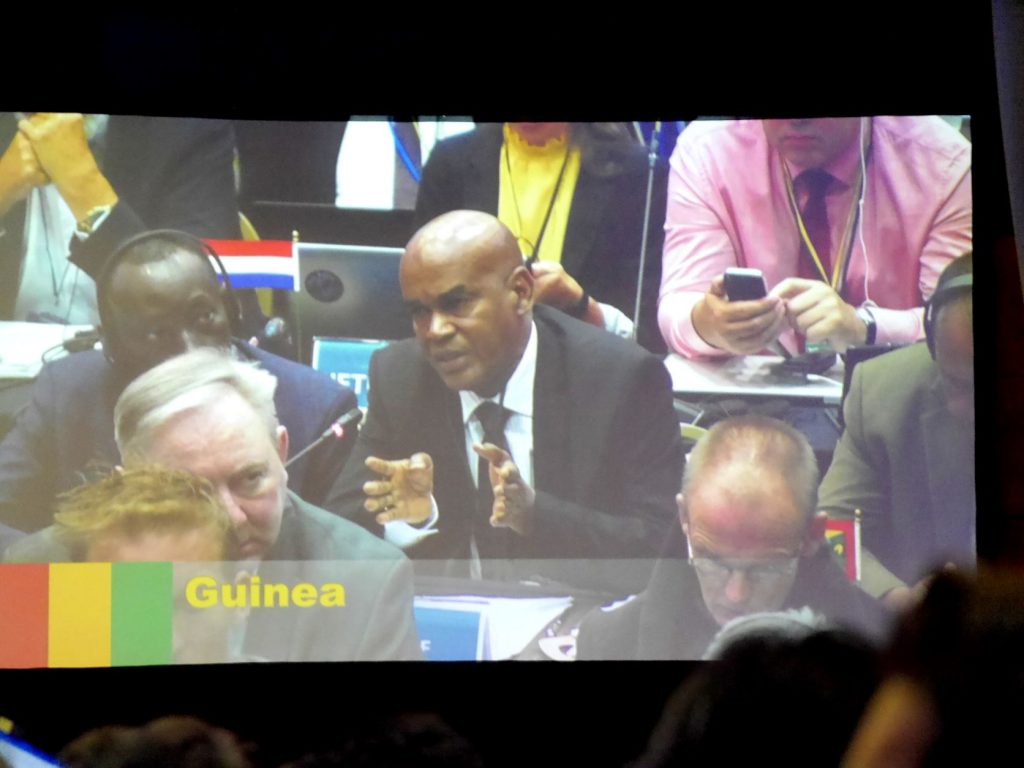

The new Chair of the International Whaling Commission is Amadou Telivel DIALLO, Republic of Guinea. He was elected at the October 2022 meeting.

Mr. Diallo has attended the IWC since the 1990s. During those years he has been a vocal advocate for the sustainable use of whales. He has also championed the interests and concerns of developing countries.

It is significant that he is chairing the IWC at this time. There is a paradigm shift in international negotiations that the author has been discussing in this article series. In other words, there is now a growing questioning of and opposition to the global standards led by the developed countries of the West.

In what direction will ー or should ー Mr. Diallo lead the IWC during his two-year term as Chair?

Needless to say, his is an important task. He must establish a mechanism to ensure that developing countries, especially those that support sustainable use, can participate fully and reliably in IWC discussions and decision making.

That alone will not be enough, however.

For Chair Diallo, who is from a developing country, it should be his mission as well as an opportunity to provide guidelines for steady and balanced implementation and compliance with the provisions of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling in the IWC. That is where countries with very different and conflicting views on whales and whaling participate and are deeply divided.

Working Group on Operational Effectiveness

In fact, the germ of a concrete measure to this end has already been presented. It is in the form of proposals of the Working Group on Operational Effectiveness (WGOE).

The working group was established to implement a number of recommendations submitted by external experts in 2018 following the IWC’s performance review. It should be Mr Diallo’s mission to put these recommendations into practice, and to ensure that the interests and rights of developing countries are respected to the fullest extent possible in the process.

While the WGOE proposal includes many items, two are particularly notable.

One is the establishment of a Management Committee as part of the organizational and operational reforms.

The other is the creation of a strategic plan and work plan for the IWC in relation to these reforms.

It is not difficult to imagine that the future of the IWC will be determined by these issues. And it will be important to see how the new IWC Chair Mr Diallo will lead the organization through these challenges.

End of series.

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW | Japan Whaling Expert: Sustainable Whaling as ‘Ideal Option’

- Revisiting the Roots of the Whaling Issue: The Relationship Between Humans and Nature

This article is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research in Japan. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.

(Read the four part series in English and in Japanese.)

Author: Joji Morishita, PhD