Two substantive issues were on the agenda for decision at IWC69. One relatively uncontroversial decision sets limits on aboriginal subsistence whaling. The other proposed a sanctuary where no whaling takes place anyway, raising questions about underlying intentions.

Are these enough to justify the perpetuation of the International Whaling Commission?

Third of Five parts

First: IWC69 Report: Has the International Whaling Commission become a Zombie?

Second: IWC69 Report: Main IWC Agenda Items of the Session

Fourth: IWC69 Report: Nonbinding Resolutions

Conclusion: IWC69 Report: What the Results Show Us

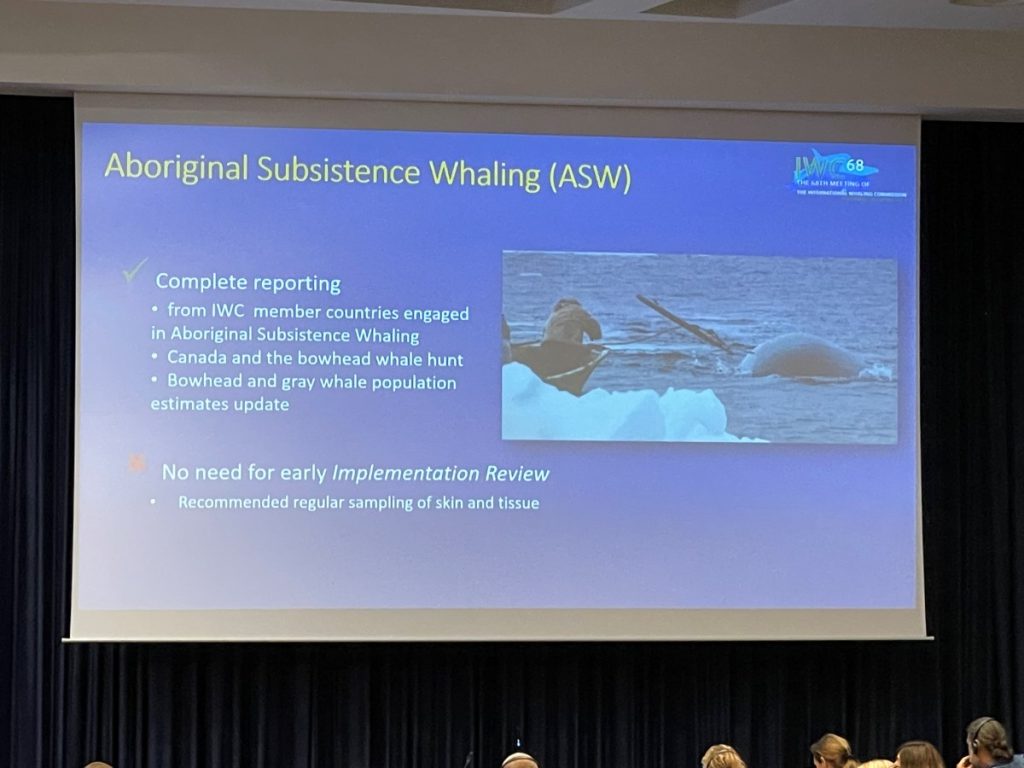

Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling Strike Limits

IWC69 was in the year of the renewal of the Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) strike limits. Since 2014, these rights have been recognized every six years for Indigenous people in the United States, Russia, Denmark (Greenland), and St Vincent. This renewal of ASW strike limits takes place as an amendment to the Schedule of the Convention and requires a three-fourths supporting vote.

On the surface, anti-whaling nations and anti-whaling NGOs are in favor of allowing whaling by indigenous peoples. However, the countries conducting ASW by indigenous peoples are confronted with challenges and issues each time the strike limits are discussed and renewed. Burdens are imposed through scientific discussions on the stock status of the target whale species, the demand for information to prove the necessity of whaling for the survival of indigenous peoples, and discussions on whaling methods, etc.

The renewal of the ASW strike limits is an important issue for the IWC as a whole. Relations with indigenous peoples are a politically sensitive and important issue for the governments of any country.

A More Sustainable System for Indigenous Whaling

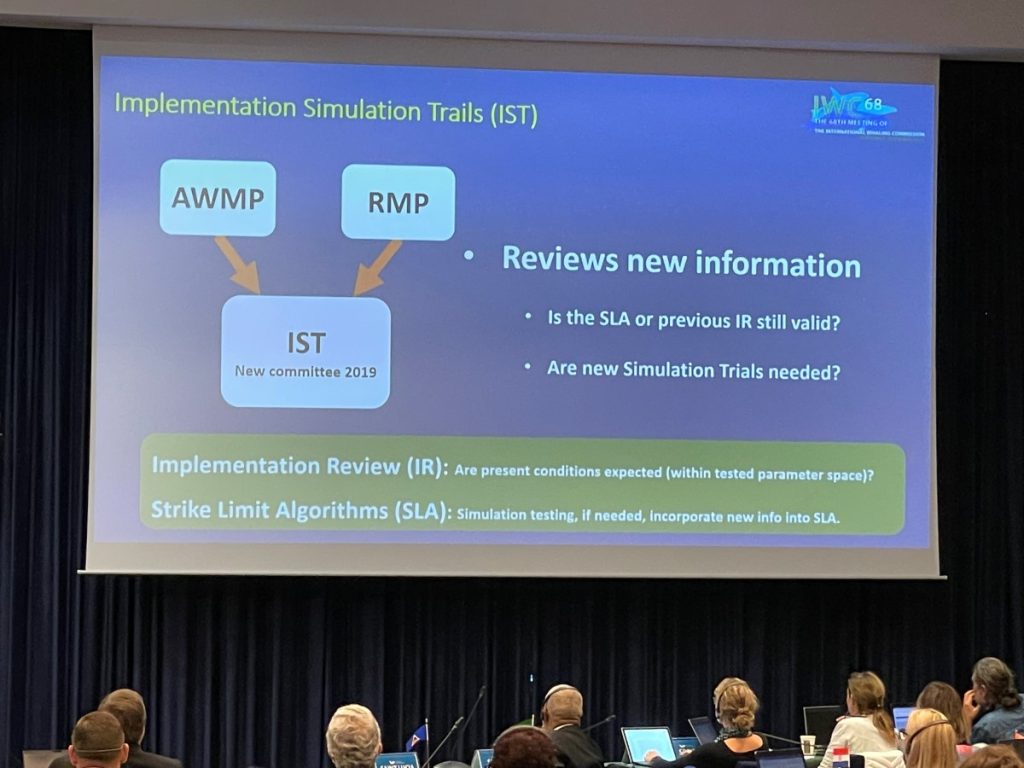

There was a major development at IWC67 in 2018 regarding the renewal of the ASW strike limits. A proposal was adopted to amend the Schedule to allow automatic renewal of the ASW strike limits if certain conditions were met. It will greatly reduce the risk of ASW nations being exposed to potential refusals in each strike limits renewal year.

The adopted automatic renewal provision (paragraph 13(a)(6) of the Schedule to the Convention) is as follows;

(6) Commencing in 2026, and provided the appropriate Strike Limit Algorithm has been developed by then, strike/catch limits (including any carry forward provisions) for each stock identified in subparagraph 13(b) shall be extended every six years, provided:

(a) the Scientific Committee advises in 2024, and every six years thereafter, that such limits will not harm that stock;

(b) the Commission does not receive a request from an ASW country relying on the stock (‘relevant ASW country’), for a change in the relevant catch limits based on need; and

(c) the Commission determines that the relevant ASW country has complied with the approved timeline and that the information provided represents a status quo continuation of the hunt.

Simply put, the provision is that strike limits will be automatically renewed without a vote if the listed conditions are met.

However, this provision was not easily adopted. As IWC67 ultimately failed to reach a consensus on the automatic renewal provision, the matter went to a vote. The Buenos Aires Group (BAG) of Latin American countries presented the strongest resistance. They opposed the proposed auto-renewal provision.

First ‘Automatic Renewal’ of Indigenous Strike Limits

IWC69 was the first occasion for the automatic renewal of the ASW strike limits rule to be applied. The ASW countries, led by the United States, came to the meeting with all possible preparations to ensure the successful application of this rule. It is not difficult to imagine the challenges involved in winning the automatic renewal over the opposition of the BAG. Meanwhile, due to the invasion of Ukraine, communications between the US and Russia were by no means easy.

Before IWC69, the relevant ASW countries stated by the deadline that they would not seek any changes to the strike limits for the next six years. The Scientific Committee also recommended that the status quo strike limits would have no negative impact on the stocks. Two of the three conditions for the automatic extension had been met, and the only one remaining was that the IWC69 meeting “determines that the relevant ASW country has complied with the approved timeline and that the information provided represents a status quo continuation of the hunt”.

Discussions in the Commission proceeded uneventfully, albeit with some tension. Since no country objected to the last condition being met, the automatic extension of the ASW strike limits was realized. Administratively, the years to which the strike limits apply were rewritten. These were contained in paragraph 13(b) of the Schedule of the Convention (from 2019 to 2025 before the automatic extension, and from 2026 to 2031 with the passage of the automatic extension).

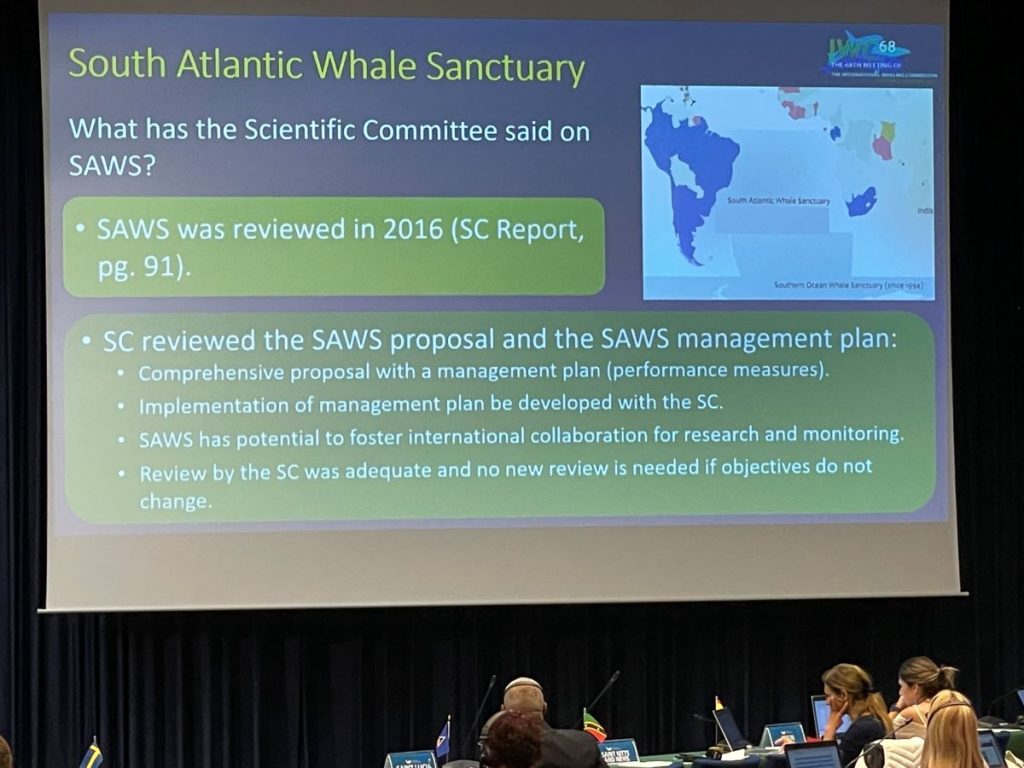

Proposal for a South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary

As mentioned above, the adoption of the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary proposal has been a long-held desire of the Latin American countries (Buenos Aires Group (BAG)). In particular, IWC69 was held in Peru, in their home region. Also, the possibility of obtaining the three-fourths (75%) of the votes required for adoption was increasing. Therefore, IWC69 was truly a full-fledged and high-expectation event for them. It would also be a major political achievement for the BAG if the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary was established at the IWC meeting held in Peru.

However, at the beginning of the meeting, it was decided that the quorum rules would be maintained in their present form. If the number of anti-whaling nations participating in IWC69 fell below the quorum of 44, there remained a possibility that the pro-sustainable use side would be able to block the vote on the proposal to establish the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary, as they had done in the previous IWC68. Anti-whaling nations were wary of this.

After the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary proposal was introduced on the first day, it was brought up for decision on the fourth day of the Commission. Reading how the votes would go changed from day to day on both sides. In the interim, some countries paid their dues and regained their voting rights. Other countries arrived in Peru in the middle of the Commission meeting. Some countries had participated but were in the process of making corrections to their incomplete credentials (official documents confirming their participation eligibility).

‘Sustainable Use’ in the Sanctuary Debate

The group of countries supporting sustainable use also met frequently to read votes and confirm their strategies. Finally, they decided to join the vote on the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary proposal.

The result of the vote was 40 countries in favor of establishing the sanctuary, 14 opposed, and 3 abstained. Because less than three-fourths of the votes were in favor, the proposal was rejected. However, the yes vote amounted to 74.1% (40 divided by (40 + 14)), so it was a truly paper-thin rejection. The vote at the IWC was a roll call (each country was called out one by one to express its position of approval, disapproval, or abstention). The results are directly reflected on a large screen in the hall, and there was considerable tension as the voting proceeded.

It is fair to say that the anti-whaling nations, although disappointed, accepted the outcome of the vote without hesitation. They are now more hopeful and confident, however, that the proposal will be adopted at the next IWC meeting in two years.

For the countries that support sustainable use, although the proposal was rejected, the result was still too close to call. The conclusion of the meeting was a painful reminder of the need to begin identifying problems and addressing them now in preparation for the next meeting.

Read the Next in the Series: IWC69 Report: Nonbinding Resolutions

RELATED:

- An Argument for Sustainable Whaling: The Case of Alaska’s Indigenous Peoples

- INTERVIEW | Japan Whaling Expert: Sustainable Whaling as ‘Ideal Option’

The series is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research in Japan. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.

Author: Joji Morishita, PhD

Former Professor, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology

The views and policies expressed in this article are the author’s own and may differ from those of the Japanese government. Any misunderstandings or errors contained herein are the sole responsibility of the author.