Fourth in a series of five articles

Part 1: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: Natural Resources and Root of Manufacturing

Part 2: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: The Power of the Warrior Spirit

Part 3: Whales in the Japanese Landscape: A Test of Character, Past and Present

The Japanese have been hunting whales since ancient times. It is impossible to consider the relationship between the Japanese people and the sea without examining the history of whaling.

This is the fourth of a series of five articles on “Whales in the Japanese Landscape.” The series is part of a larger ongoing collection published by The Sankei Shimbun in Japanese, titled “Tales of the Watatsumi” after the Japanese god of the sea.

In this article, we take a look at the questions of ownership of the whales that were caught and traditions in distributing the bounty of the seas.

Japanese whalers of the Edo period made huge fortunes. In a way, these men monopolized an ocean resource that belonged to no one. Apparently, other groups then stole the meat of captured whales, but they were not severely punished.

It was an era before modern laws were established. This could be thought of as an impromptu distribution network for a valuable natural resource.

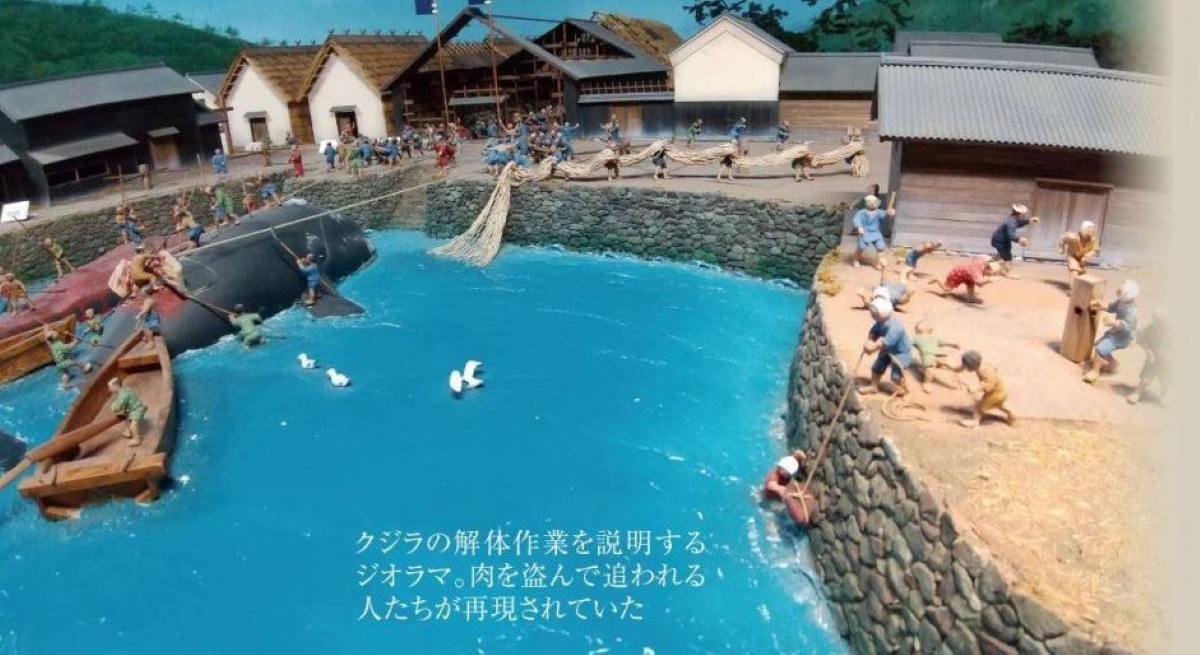

What caught my attention was not the flensing of a giant whale portrayed in the diorama exhibit, but rather a small group shown in one corner. I was visiting the Shima no Yakata Museum on Ikitsuki Island in Hirado City, Nagasaki Prefecture. During the Edo Period, this was home to one of the largest traditional whaling operations in all of Japan.

The group that caught my eye was sneakily hanging a net over the side of the wharf, attempting to snare chunks of whale meat in the water. They were also trying to evade men chasing them with raised clubs. Could this be a gang of thieves?

Kyushu Whalers

During the late Edo period, the scale of whaling operations in the northwest part of Kyushu surpassed those of Taiji and other communities in the Kishu region (near modern Wakayama).

Kyushu whalers included the Masutomi clan, which ran a large enterprise based on Ikitsuki Island, but also had whaling groups that operated on Iki Island and the Goto-nada Sea west of Kyushu, employing some 3,000 people. The operation used a modern management style that sought to increase capacity and efficiency, recruiting fishermen skilled with using nets from around Kyushu and further north in the Setouchi region on Japan’s main island of Honshu.

Under the management of the Masutomi clan, traditional whaling, which had first developed during the pre-Edo Warring States Period in Ise Bay near modern Mie Prefecture, reached its zenith.

Painter and Dutch scholar Shiba Kokan visited the Masutomi operation for a month in 1788. His “Saiyu Nikki” (Diary of Western Travels) contains a description of the prosperous scene:

The eight-oared boat shot forth as though it was flying, as the rowers cried out “Ariya! Ariya! Ariya!”

His vivid descriptions capture his astonishment at details such as the speed when he rode along on a Sekobune whaling boat. Such aspects are not portrayed by the diorama exhibit.

A Marine Monopoly

“This is called kandara.”

Museum Curator Shigeo Nakazono explains that the phrase is used to describe the actions of groups that sought to steal fresh catches from the harbor. Thefts were a common practice across coastal communities, although they were referred to by different names and have become the subject of ethnological studies.

While fish were a shared resource among the residents of fishing communities, when whaling groups formed, they monopolized their catches. The local residents became their employees. Even so, the practice of stealing such catches has deep roots and has long been recognized in such communities. Nakazono describes it this way:

Whaling operations had monopolies on their catches and sought to generate profits from communities in which they were outsiders, so the practice of kandara was generally tolerated.

Hidden Meanings in Ownership and Distribution

It seems that within the practice of kandara is a fundamental but hidden meaning related to ownership and distribution.

A practice that is almost the exact opposite was observed in the whaling community of Utqiagvik village in Alaska by Nobuhiro Kishigami, a professor at Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology.

In the village, groups of seven or eight individuals team up to hunt whales in the spring and fall. Meat from the hunts is generously distributed among the village residents. Feasts are held for family and relatives where meat is given away as a gift, and even individuals from other villages are invited to come and collect their share. Meat is delivered to those who are unable to come, such as the elderly and widowers.

Whaling is not carried out for profit, and whalers even spend the wages they have earned from other jobs on the hunts, for which they must cover all their expenses.

“For these men, hunting whales and sharing the meat among the community is itself a meaningful practice. The distribution of the meat plays an important role in connecting the people of the village,” explains Professor Kishigami.

There are about 45 whaling groups in the Alaskan village, and the locals often receive the benefits of the hunts. According to Kishigami, with customs like this, it is difficult to imagine that someone there would steal whale meat from another.

Local Benefits

When I gaze again at the figures in the diorama, they now look like glorified thieves. They pulled whales from the ocean and claimed the catch as their private property. These whales were a resource that belonged to no one, and thus belonged to everyone.

Men that claimed the whales shifted the rules of the sea in their favor. They had the skills and strength to establish a successful system for catching whales, but hoarded the blessings of the sea for themselves. I feel deeply that it is perfectly logical to think of this practice as an extravagant theft.

This was a time before modern laws.

It appears that the whalers felt the need to pay off this debt. The painter Kokan records that on Ikitsuki Island, small buildings were constructed near the shore where public theater performances were held. Some members of the Masutomi family put on comedic puppet performances. It is said that when “joruri” samisen performers visited the community it caused local pandemonium, with hundreds of men and women, young and old, pushing and shoving to see the show.

The Masutomi clan paid large taxes to the Hirado authorities, driving the local economy. They contributed to the region in a variety of ways, creating new rice fields, building seawalls, and funding the construction of new tori gates for local shrines.

Pretend ‘We Didn’t Notice’

Other whaling clans in Kyushu also made local contributions, enforcing bans on fighting and gambling. And they created moral laws to regulate the actions of fishermen from outside the community, such as prohibiting fishermen from wandering around the villages where they were employed. It seems that the whalers worked hard to prevent local opinion from turning against their naked pursuit of profits.

This was also true in Taiji, where whaling was run by the Wada and Taiji families. In a public speech recalling his young days during the Meiji period, Gorosaku Taiji said his mother gave him strict advice to follow regarding the local community: “Usually we must allow them to cut off pieces (of whale meat) for themselves, acting as though we didn’t notice.”

The Flensing Grounds

Not a single building remains on the cove where, in the old days, whales were flensed and cut up into meat. All that is here now is a concrete sea wall and a field sprinkled with grass.

It is here that Kokan observed the cutting up of a right whale, admiring the orderly processing of the various sections of the animal and noting that “not a single part of the whale is thrown away.”

I wonder if he saw kandara? It seems as if countless emotions rise from beneath the field before me, where the grass sways in the strong wind.

(Read the column in Japanese at this link. This article is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.)

Series continues in Part 5.

RELATED:

- Whales in the Japanese Landscape: Natural Resources and Root of Manufacturing

- Rare Artwork from the Baleen of Whales

Author: Hideaki Sakamoto