Female Company President Brings New Wave to the Waste Industry

An interview with Reiko Futagi, CEO of Tokyo-based Otani Seiun, K.K., on promoting sustainable lifestyles and revamping the waste industry by empowering women.

このページを 日本語 で読む

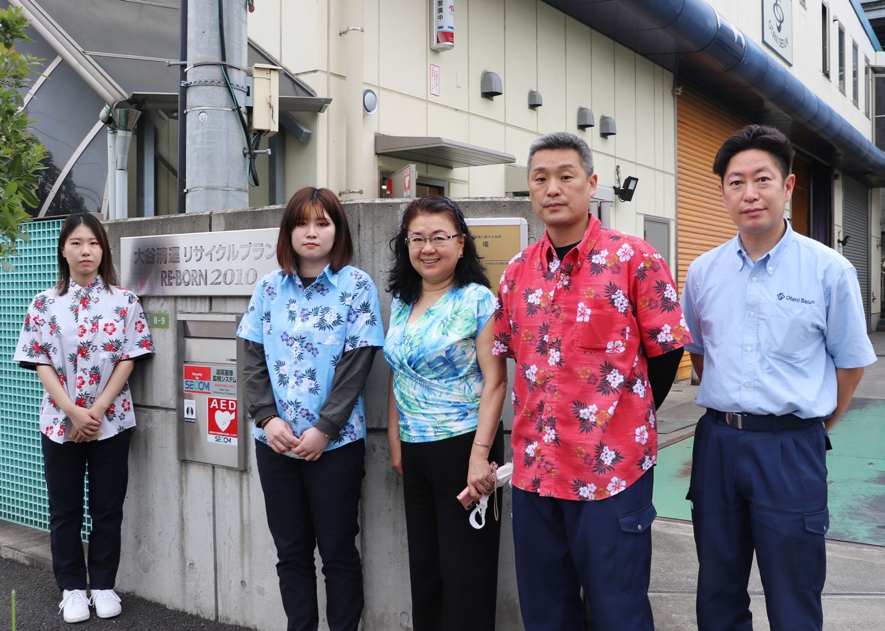

A woman of Katsushika Ward in Tokyo inherits her father's waste collection business and transforms it to include recycling and product creation. Her name is Reiko Futagi, President & CEO of Otani Seiun K.K.

Her company's roots lie in the waste collection from Washington Heights, a housing complex for US Occupation forces, established in Tokyo shortly after World War II.

In addition to proposing ‘Re-Slim,’ a lifestyle designed to slim down consumption, Futagi is working to establish a women's council within the Japan Federation of Industrial Waste Management and Recycling Associations, to improve the status of women in the industry.

Roots in Post-War Tokyo’s ‘American Town’

After the war, a housing complex was built for officers of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ) and their families on the burnt ruins of a training camp in Yoyogi, Tokyo.

The 924,000-square-meter Americanized town of Washington Heights was comprised of 827 units that were fully furnished and equipped, even with kitchen utensils. The occupants led typical American lifestyles, disposing large quantities of leftover food, paper, metal, and other waste.

Otani Seiun traces its roots back to Washington Heights, where it collected leftover food to use as feed in pig farming and empty cans to use as recycled raw material for steel manufacturing.

Originally the waste division of a group company of Otani Heavy Industries (formerly Otani Kogyo), the company was started by Yonetaro Otani, who was also the founder of Hotel New Otani, one of Japan's leading hotel chains.

Reiko Futagi's father took over the business in light of a government request to establish Hotel New Otani in preparation for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. This marked the beginning of Otani Seiun.

I understand that your father was not a blood relative of the Otani family, so how did he establish your company?

My father worked for Otani Kogyo and was in charge of procuring raw materials for rolled plates, utilizing cans and steel from Washington Heights.

Many companies that collected food waste from Washington Heights, including Otani Kogyo, were also in the pig farming business. But, all 55 companies became obsolete when the GHQ left Japan and Washington Heights was closed.

Faced with the lack of work, Otani Kogyo and several other companies were granted rights to operate as cleaning businesses in the metropolitan area of Tokyo.

Once Yonetaro Otani entered the hotel business at the government's request, my father took over this metropolitan cleaning business. The ‘Seiun’ (written as two characters that roughly translate as ‘clean’ and ‘transport’) in Otani Seiun dates back to this time.

To this day, our company is entrusted with waste collection and disposal for Hotel New Otani and the group. This year (2022) marks the 60th anniversary of our company.

You previously were employed at Hotel New Otani. What made you decide to take over Otani Seiun?

I attended Nihon University’s College of Art and instead of hunting for work after graduation, starting working for Hotel New Otani where I had a connection. I worked in sales there for ten years.

My department was located near the office of the general manager, the third generation of presidents from the Otani family. Witnessing the president's work on a daily basis, I became interested in management.

My father was also a manager, albeit of a small company. So I quit the hotel and joined Otani Seiun.

Shifting Gears to ‘RE-BORN’ Plants

It was Futagi's idea to expand the business from collection and transport to recycling.

How did you become interested in the environment?

During my days at Hotel New Otani, I had a British woman colleague, and her seriousness toward the environment was eye-opening for me. Then in 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

I strongly felt that our work was directly related to the environment and that I wanted to do something about it.

At the time, our company was merely collecting waste and transporting it to disposal sites. I wanted to do more than that – I also wanted to convert waste into resources. But, to do this, we needed both space and facilities.

We began looking for a suitable location and learned of a site in the Iriya district of Adachi Ward. The district is not residential but semi-industrial, with many waste-related plants.

In 2000, our company started renting this site, which covers an area of roughly 2,000 square meters, and the plant built on the property. We built an intermediate treatment facility starting with the installment of a crushing machine.

We subsequently introduced a plastic bottle compressing machine, and took charge of "bottle-to-bottle" recycling for Adachi Ward, via which PET bottles are baled and taken to a recycling facility.

Later we began sorting plastic containers and packaging for Suginami Ward. Our government clients and requests for compressing work have increased.

When the enlarged scope of work caused us to outgrow our facility, we had to take out a loan (from a bank) for the first time. It was unfortunate, considering my father had always maintained a debt-free business.

So, in constructing the plant, you struggled to gain the support of nearby residents?

The construction of our second plant was challenging due to relationships with neighboring residents. There was opposition to the project, questioning why a contractor from Katsushika Ward was coming to Adachi Ward.

Activists who were not residents joined in, further complicating the situation. We held many explanatory meetings and changed our design plans, despite the increased costs.

A former board member at a paint manufacturer was one of the members of the neighborhood association. When he learned that we would install a machine to convert waste into RPF (refuse derived paper and plastics densified fuel), he deemed our project to be ‘necessary for the future,’ which turned the tide.

It took about a year to get approval, but we opened our second plant in 2010.

In response to the request of residents, we open the facility to the public once a year. We built a pathway for tours to ensure transparency.

We also sponsor local events such as the Bon Odori dance festival, providing both manpower and vehicles. Now, we have an excellent relationship with the locals, to the point where they say they are glad Otani Seiun moved to their district.

Currently, you have four plants and each is named ‘RE-BORN’, followed by the year of establishment. What is the meaning behind these names?

We chose the name ‘RE-BORN’ to signify giving life to waste once again by making use of it to the utmost extent possible as a valuable resource.

Upcycling Plastic Umbrellas

On rainy and windy days, broken plastic umbrellas can often be found abandoned along the road. Cheap plastic umbrellas can be lifesavers during sudden rainstorms, but most of them are not recycled. So, Futagi developed an upcycled product using these discarded plastic umbrellas.

You worked with students in a class at Bunkyo Gakuin University to creatively upcycle discarded plastic umbrellas. Why?

When I came up with the name RE-BORN, I knew that eventually, I wanted to be involved in not only intermediate processing, but in creating recycled plastic products as well.

At a cross-industry exchange meeting, I became acquainted with a person from the Japan Umbrella Promotion Association (JUPA). I asked about recycling discarded plastic umbrellas.

Plastic umbrellas are difficult to recycle due to their metal ribs. After consulting with a professor at Bunkyo Gakuin University who specializes in environmental issues, we decided to try to upcycle discarded plastic umbrellas as a way to reduce plastic.

We worked with students as part of a class at the university's Social Design Center, which focuses on solving social problems.

Mondo Design (Minato Ward, Tokyo), which makes bags from plastic umbrellas, cooperated with us to create a prototype for an umbrella holder, an idea developed by the students.

The holders are designed to help reduce the use of plastic umbrella bags, which are commonly used to prevent water from getting on floors. Although the product was not commercialized, I believe it was meaningful.

‘Re-Slim’ Lifestyle of the Future

At company president Futagi's suggestion, a new planning division, called ‘Re-Slim’ was created in the company. Designers and others in the division plan waste separation workshops, create waste separation-related designs, and produce educational videos on recycling.

What is the meaning of ‘Re-Slim’?

‘Re-Slim’ is about ‘slimming’ down consumption and waste. It implies a lifestyle of choosing items that last, rather than those quickly discarded.

It is not about mass production, mass consumption, and mass disposal, but about living a rich life with the few things you like and carefully select. This is the ‘Re-Slim’ lifestyle that we will continue to promote.

For example, bags are commonly lined with metal to protect coffee beans and tea leaves from exposure to moisture, but they are difficult to sort and recycle. Although bags with added functions have been developed in response to manufacturers' needs, they should also be made to be easier to recycle.

Consumers should also have an eye for selecting products geared to a circular economy.

Raising the Status of Women

There are not many women in the waste industry. Have you faced any challenges?

The reality is that the status of women in this industry is low.

In the Japan Federation of Industrial Waste Management and Recycling Associations, only 13 of 47 prefectures have women's subcommittees. When I asked about female members in each prefecture, I was bluntly told, “there aren’t any women in this industry.”

However, small and medium-sized enterprises make up the industry, and it is not uncommon for women to take over companies. It’s not that there are no female members, but that we are often blatantly disregarded.

A lack of human resources is one of the industry's biggest concerns. The fifth goal of the SDGs is gender equality and women’s empowerment. If women thrive in the industry, more men will join them in their efforts.

In November of this year (2022), I aim to establish a women's council within the Federation, to serve as a national network of women working for women’s empowerment and the development of the industry.

このページを 日本語 で読む