[Global to Local] Rogier Uitenboogaart: The Art of Japanese Papermaking in Kochi

Dutch washi artisan Rogier Uitenboogaart employs sustainable and traditional techniques in his papermaking, utilizing resources from the nearby satoyama.

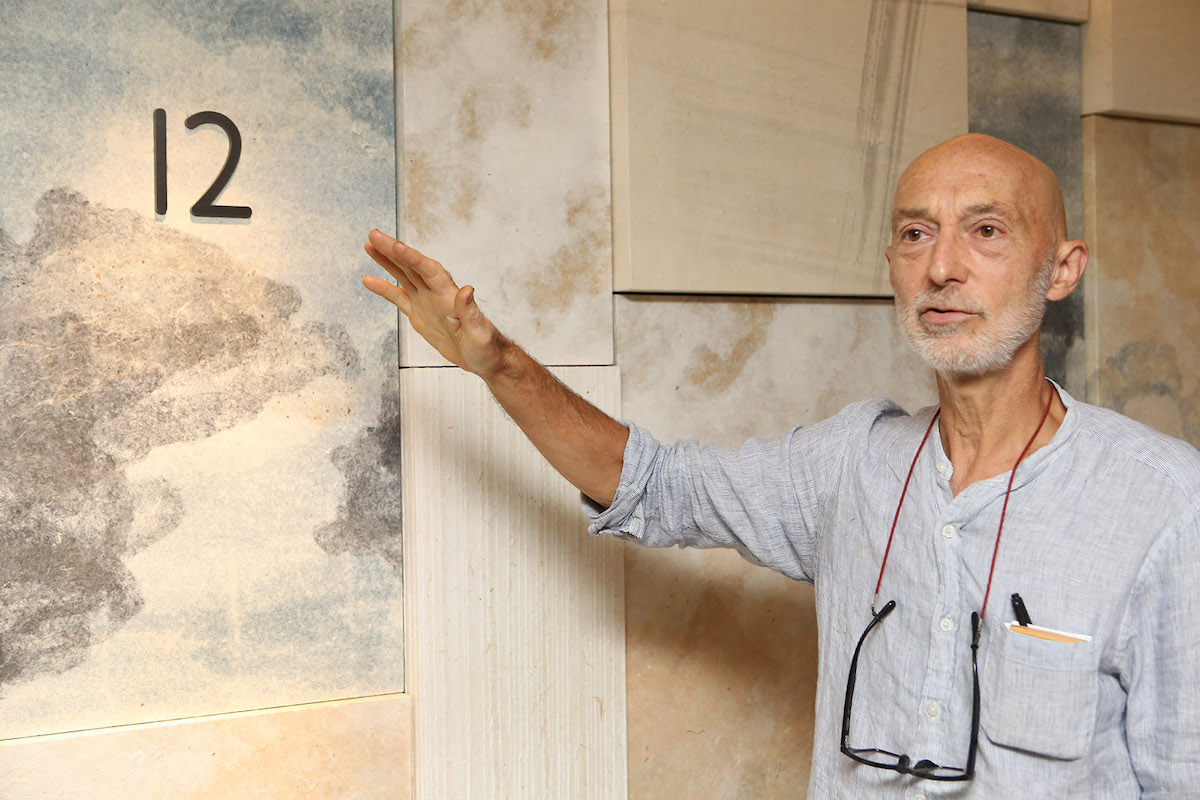

Kamikoya Washi Studio is located in a nature-rich region of Kochi Prefecture, surrounded by forest and close to the sparkling Shimanto River. Owner Rogier Uitenboogaart handles every step of the papermaking process without chemicals or machinery, from growing the raw materials to producing his traditional washi paper.

Uitenboogaart, who hails from The Hague in the Netherlands, came to Japan more than 40 years ago to learn the art of Japanese papermaking. In addition to producing washi for use in interior design and furnishings nationwide, Rogier and his family welcome guests who come to Kamikoya for hands-on papermaking experiences and to stay at the Japanese-style guesthouse.

Coming to Japan

What originally attracted you to washi?

I first saw some at the bookbinding company in Amsterdam where I was working, and I was intrigued. In fact, washi had been used in Europe for several hundred years, and Dutch painter Rembrandt used it in the seventeenth century. However, there was nobody who could really teach me more about it, and with no Internet in those days, I had to come to Japan to learn more.

Were you interested in Japanese culture at the time?

Not so much at first, but then it seemed that the universe began pointing me in that direction. For example, I'd start noticing media articles about Japan, or I'd run into people who had just come back from Japan. I was also inspired after reading a book by Masanobu Fukuoka (1913 to 2008), a Japanese farmer and philosopher who pioneered the idea of natural farming.

After arriving in 1980, you traveled to various places at first to learn about washi and met your wife. Why did you eventually settle in Kochi Prefecture?

Kochi Prefecture is Japan's second biggest washi producer after Fukui. The traditions of washi papermaking were still alive in Kochi, along with a spirit of innovation, and we liked the climate here. I built my first studio in 1992 in the town of Ino. (Ino and nearby Tosa City are two of Kochi’s main washi-papermaking centers.)

A Family Business

When did you move to your current location in Yusuhara Town?

We made the move in 1992 and established a new studio. In 2006 we added the guesthouse to accommodate people coming for workshops. We chose Yusuhara because of the greater proximity to nature here, including the Shimanto River. Also, because of the more distinct seasons, we have a longer optimal period for papermaking each year.

What do you love about where you live?

While, of course, it's not quite the same as when we first moved, the pace of change has been very gradual. There is still a feeling of living with tradition, with the ways of the past. I loved this aspect when I first came to Yusuhura, and I still do! Both the people and the food here are wonderful, too.

Kamikoya, your studio, is a family-run business, right?

Yes, my wife and our son work with me, and we have several other people coming in two or three days a week, too.

A beautiful cat is introduced as one of the "staff" on your website. How does the combination of cats and washi work?

We have Tsuki, the cat on the website, as well as her son. Kamikoya's paper is so strong that the cats can climb to the top of a shoji door. Tsuki is actually more interested in scratching our wooden beams and has left her mark in that way! But she's an important member of the team and very friendly. She greets all our visitors when they arrive.

Papermaking and More

What are the main uses for your washi paper?

For interior goods, such as wallpaper, lamps, and shoji (traditional paper-covered sliding doors used in Japanese homes), and paper for artistic purposes such as printing, calligraphy, and collage. It’s also used as part of artwork itself.

Tell us about the guests who come to Kamikoya.

The majority come for a basic papermaking experience of 1.5 to 2 hours. Our guests are a diverse mix of ages and nationalities — families, seniors, young people, solo — from Japan as well as from around the world. One young Japanese woman who first tried papermaking at our workshop went on to study the craft in Ehime and has written a book about her experiences.

What is the most challenging part of your activities?

For one thing, we always have to adjust to the weather and nature. In terms of our papermaking, we follow about 30 steps in a year-long process. Getting things right at every one of those steps is a challenge. We never stop learning!

A Culture of Sustainability

How does the papermaking process connect to sustainability?

For example, to extract the fiber from the plants, we steam them and peel off the outer layers, heated by firewood from the forest around us. From beating the fibers to pressing and drying the sheets of paper on wooden boards, we're not using any chemicals or machinery. These traditional methods are not only environmentally friendly, they make the strongest, most durable paper!

Along with using your home-grown fiber plants as raw materials, you also make use of cotton. Where does that fit in?

Ikeuchi Organic is a company in Imabari, Ehime that makes towels from organic cotton. We use the leftover cotton from their production process in some of our washi. The cotton connects to traditional Dutch papermaking techniques, where old cloth was recycled into paper. Cotton makes it easy to create thicker paper for Western-style art, such as lithographs and etchings. It also allows greater possibilities for my own pulp painting artwork.

Are there many people still crafting washi paper with traditional methods and growing the plants to make them?

While we are still only a second-generation business, there are papermaking families who go back several generations. You do see some of the younger people coming back home to Kochi to help. There are fewer plant farmers, however, and the average age of the remaining farmers is around 80. A washi maker can be a designer or a paper artist, and those things have a "cool" image. But not so much with the farming side, perhaps.

New Developments

Tell us about some of the special projects you've been working on.

Last year a Dutch TV crew came to film for a very popular show. And while we can't yet say too much, we are currently in the process of working for an international fashion brand on some items for their 2024 spring collection.

Essentially you are preserving traditions while developing ideas that fit into modern life?

Exactly. As an example, one of our partners is the Ginza Honey Bee Project, an NPO that began with urban beekeeping on building rooftops in Tokyo's Ginza district. They grow the fiber plants, which are sent to us after harvesting to make paper. We are cooperating to promote these endeavors, the products, and washi culture as part of a satoyama. This connection has led to our paper being used for art panels at one of Marriott's hotels, the AC Hotel Tokyo Ginza. We need to show people that you can make a living. Otherwise it's just, "Oh, cool, you're preserving traditions," and it ends there. When you mention big names and tell them you can earn money from this, it sparks their interest.

For more information, visit the Kamikoya Washi Studio website.

Check out other installments of Global to Local by Louise George Kittaka.

Louise George Kittaka is a bilingual writer and content creator from New Zealand. She writes for a wide range of media platforms and also lectures at Shirayuri Women’s University in Tokyo. Louise loves waterfalls, sweet buffets, karaoke and traveling, and is obsessed with the Aliens movies.