In October 2022, the 68th meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was held in Portorož, Slovenia. IWC68 was also the first meeting in which Japan, which withdrew from the IWC in 2019, participated as an observer.

This first session in four years brought attention to the IWC’s changing priorities, including several points of significance that deserve discussion. These are examined in a four part series, continuing below in Part 3.

Part 1: IWC68: Reflections on the Future of the International Whaling Commission

Part 2: IWC68: An International Whaling Commission in Crisis

Part 3 of 4

The Atlantic Sanctuary Proposal

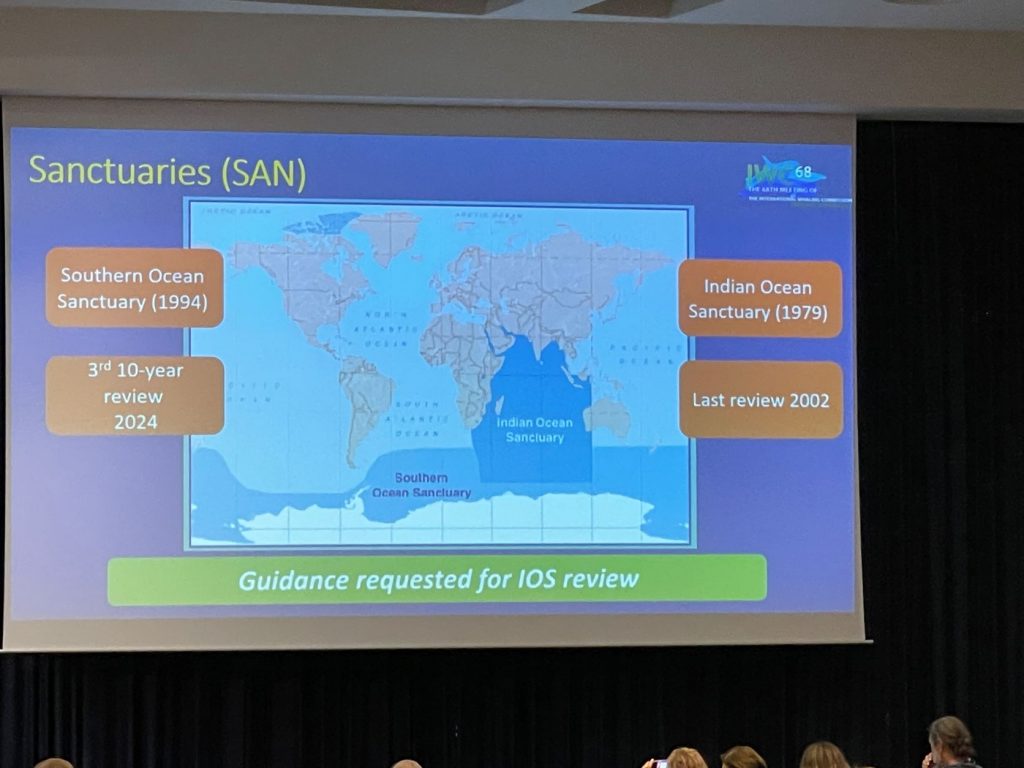

At IWC 68, the trend toward transformation into an international organization for whale protection was more evident than in the past. Since 2001, there had been a proposal to designate the South Atlantic as a whale sanctuary at almost every IWC meeting by South American nations. Yet it wasn’t pushed for adoption until the 68th meeting of the IWC.

The outcome of this debate would determine the future of the IWC as a whale protection organization. If the pro-sustainable use side could secure more than a quarter of the votes, the proposal would be rejected. Three-quarters of the votes are required for adoption of the measure.

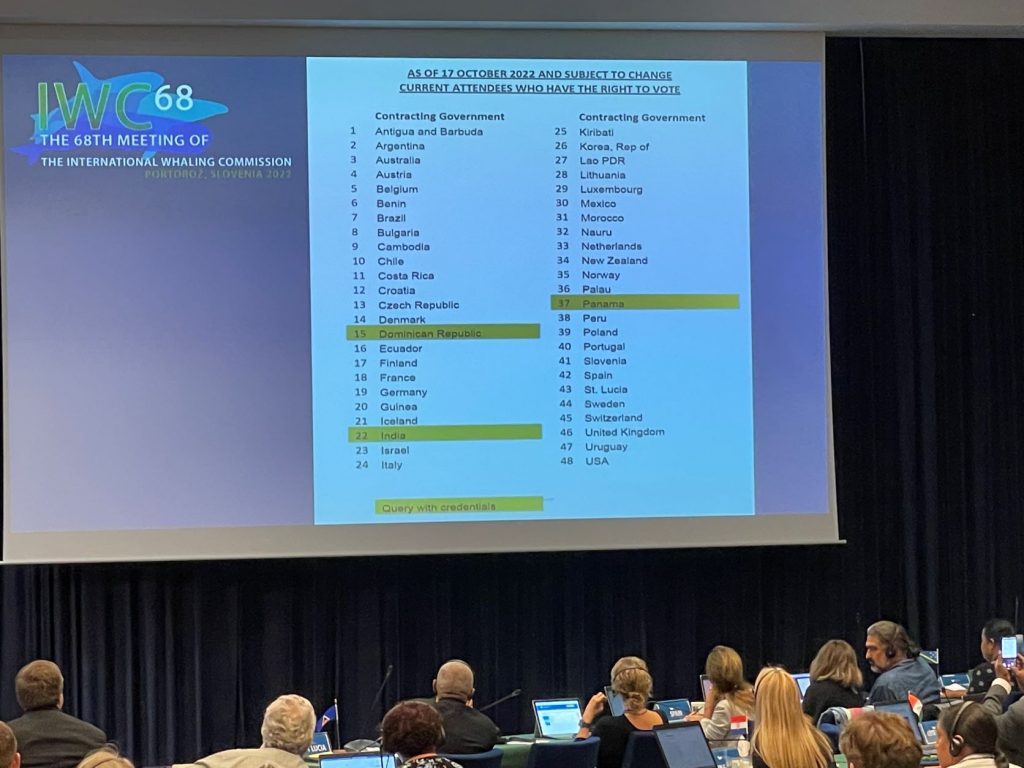

In the past, pro-sustainable use developing countries that were not economically rich were often unable to pay their contributions to the IWC and thus lost their right to vote.

In IWC 68, a special measure was introduced to allow special voting rights for countries that were unable to pay their contributions because of economic hardship caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a circumstance that many countries suffered from. This special measure allowed countries that could not afford to pay their dues to vote.

It was hoped that this special measure would allow countries supporting sustainable use to secure a sufficient number of votes to reject the South Atlantic Sanctuary proposal.

Not All Members Could Get To Slovenia for IWC68

However, the economic hardships of developing countries do not only affect the payment of contributions. Even if they regained their voting rights thanks to the special measures mentioned above, they were unable to secure travel expenses to send a delegation to Slovenia, where IWC 68 was held.

Furthermore, a number of developing countries in support of sustainable use were unable to participate in IWC 68 because of time-consuming visa procedures for entry into the EU, including Slovenia. This applied even to countries that had secured travel expenses.

We argued that this undermines the will and right of developing countries to participate in IWC decision-making, and that a vote on a controversial proposal such as the South Atlantic Sanctuary proposal should not be forced at this meeting, where they could not participate in the decision.

However South American countries were eager to call for a vote. For a decision to be made, a quorum must be present. Therefore, if the pro-sustainable use countries do not participate in the meeting, a quorum will not be met.

Indeed, after consultation, the pro-sustainable use countries decided not to participate in the meeting if a vote was to be taken.As a result, the vote did not take place and the South Atlantic Sanctuary proposal was not adopted.

Issues of Fairness

South American countries vehemently objected, saying that this was a denial of their right to a decision.

However, many countries that support sustainable use would have been deprived of their right to participate in the decision process. Shouldn’t major and controversial decisions be made with the participation of all concerned countries willing to participate?

Common sense in developed countries is not necessarily common sense in developing countries. It would be arrogant to think that what is common sense for developed Western countries is the same for all countries and should therefore be accepted.

Backlash at IWC68

At IWC68, and in the debate on the whaling issue itself, there has been a noticeable backlash by developing countries. Those favoring sustainable use find themselves pitted against the concepts and systems created and led by the Western advanced nations. That includes anti-whaling ideology.

It is true that the composition of the whaling controversy has changed partly because of Japan’s withdrawal from the Commission. However, the movement of developing countries is not limited to the International Whaling Commission.

There is a growing tension in many international forums. Part of that is opposition to rules and procedures that developed Western countries consider common sense. Too, there is a demand for review of laws and policies that Western countries push others to follow by calling them “global standards.” (This is a term often used by anti-whaling countries in the International Whaling Commission).

IWC68 Visa Controversy Highlights the Gap

The visa problem, which became an issue at IWC68 and was part of the discussions over the South Atlantic Sanctuary proposal, illustrates part of this gap.

Obtaining a visa to enter Slovenia was not easy for many developing countries. For developed countries, which in many cases do not even need a visa, the difficulties their less developed IWC colleagues faced were unimaginable.

African countries do not have a Slovenian embassy or consulate in their country. In most cases, even remote or internet applications are not accepted. Therefore, one has to go to a third country with a Slovenian embassy or consulate to apply for a visa.

Participants from the African-Atlantic countries that support sustainable use often travel to France, a former colonial master nation, to apply for a visa. They then have to wait for days for the visa to be granted.

Meaningful Participation: Perceptions and Reality Gaps

Differences of opinion between many developed countries and developing ones were brought into focus at the IWC68 meeting.

For example, developed countries argued for making a decision on financial issues and organizational reform of the IWC. Delaying the decision was unnecessary, they said, since there had been a sufficient exchange of views earlier and leading up to the meeting. On the other hand, developing countries took the position that more time was needed for discussion.

This was not a difference of position on whaling. And it was not a delaying tactic. It represented a difference of opinion on the adequacy of procedures between developed Western countries and developing countries.

Another way the difference was highlighted was in the handling of documents and materials. A common belief of Western developed countries was that holding abundant meetings, producing a vast amount of documents and materials, preparing detailed reports, and publishing these reports for comments and revisions, was enough to ensure adequate discussion and maximum transparency.

However, at IWC68 it became clear that this thinking of developed countries was not shared by many developing countries. Too often representatives of developing countries have been unable to join these plentiful meetings. In addition, they have not had enough personnel to consider the vast number of documents and reports.

Overall, the process intended to produce fairness under Western standards does not provide developing countries enough opportunity to contribute to the deliberations.

This problem is not limited to the IWC. It is a situation observed in various international meetings and discussions, including at the United Nations.

A Hard Look at Capacity Building

The international community has always recognized the need for capacity building in response to similar situations. Indeed, the promotion of capacity building is enshrined in numerous documents such as treaties and declarations.

However, is a lack of capacity the cause of the problems above, and is capacity building the answer?

More importantly, have the myriad of provisions promoting capacity building so far led to solutions to the problems?

IWC68 Puts Spotlight on Western Leadership

The author has participated in various international conferences over the years. In discussions in international organizations, not limited to fisheries organizations, the Western industrialized countries have often been the ones to take the leadership initiative. They have made the proposals and controlled the direction of discussions.

In many cases, it has been the advanced nations of Europe and the United States that have presented the latest available scientific findings and put forward the global standards.

The reality is that global standards have often meant those standards of advanced Western countries. Furthermore, reports of international conferences often have been drafted by rapporteurs provided by the participating countries, usually from the English-speaking countries.

Developing countries and non-Western countries, including Japan, respond passively to these proposals and propose revisions based on the draft report prepared by rapporteurs predominantly from those developed Western countries.

In other words, the developing countries are fighting in the arena prepared and controlled by the advanced Western countries.

It is not wrong ー and often necessary ー for countries that have the ability and resources to take the leadership. However, when the Western countries consider their own leadership and procedures to be the global standard, they widen the gap. Are they not imposing their own standards on non-Western countries? And do they realize that their own standards are not in line with developing countries’ national capacities, customs, history, and values?

Are the Western standards really the best solution?

Continues in Part 4: ‘Sustainable Use’ is the Next Challenge

RELATED:

- NAMMCO at 30: Supporting Discussions on the Sustainable Use of Marine Mammals

- An Argument for Sustainable Whaling: The Case of Alaska’s Indigenous Peoples

- NAMMCO At 30: Marine Mammals in Cultural Traditions and Identity

This article is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research in Japan. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.

Author:Joji Morishita