~~

~

While Japan suffers through one of its colder winters in memory, a small group of scientists from the country have headed to a faraway place – the Antarctic Ocean, where it is now the peak of summer, with the sun in the sky nearly 24 hours a day.

The expedition is part of Japan’s unwavering effort to shed light on the fact that certain species of whales in the region exist in sufficient numbers to be hunted sustainably. Data collected at sea has long shown that while a handful of the nearly 90 species of cetaceans are endangered, many are plentiful.

Antarctic minke whale (drone image) © Institute of Cetacean Research

Humpback whales (drone image) © Institute of Cetacean Research

In December of 2021, the research ship Yushin Maru No. 2, departed from Shiogama, a port city near Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture. The 747 ton vessel is manned by a crew of 16, along with a team of three researchers.

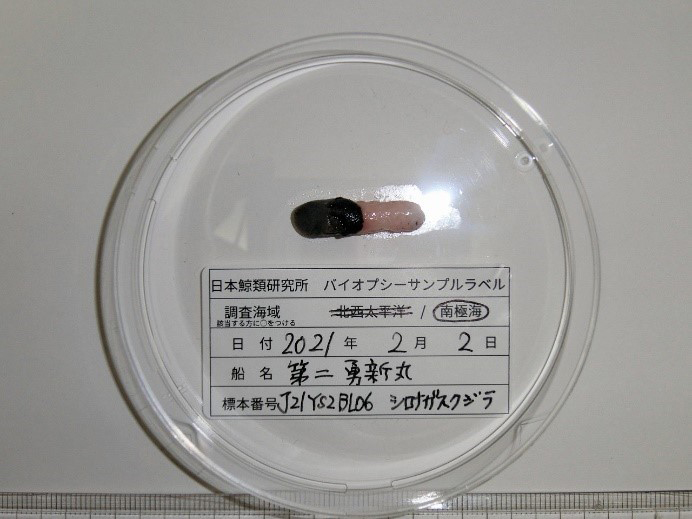

The research voyage will conduct a variety of surveys of large whale species during its more than three-month voyage. These include surveys by sight, by attaching satellite trackers and by taking skin samples for various research. This is the third consecutive survey conducted in the region as part of the ongoing “Japanese Abundance and Stock-structure Surveys in the Antarctic” (JASS-A) research project.

Blue whale (drone image) © Institute of Cetacean Research

Biopsy sampling (fin whale) © Institute of Cetacean Research

Last year’s survey, which returned to port in March 2021, spotted nearly 1,200 animals from eight species. Along with attaching trackers and collecting biopsy samples, scientists also began experimenting with drones to photograph and measure whales at sea, despite the harsh aerial conditions.

The Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR), Japan’s main research body for the animals, in December displayed a purposely designed whale research drone called the Asuka. The winged drone can take off, land, and fly autonomously in strong winds for distances of over 50 kilometers, tracking whales through previously inaccessible areas, such as among ice floes.

Examples of individual identification photos – humpback whale research. © Institute of Cetacean Research

Taking individual identification for whale research. © Institute of Cetacean Research

The notion of hunting whales remains anathema in much of the western world, where they long ago became a totem of the environmental movement. Still, scientists and environmental organizations have long stressed that ship strikes, fishing nets, sonar employed by military vessels, and ocean pollution all present far greater dangers to cetacean populations than the limited hunts carried out by modern whaling nations and native communities today.

Japan has for decades collected and submitted data on whale populations to international bodies such as the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The country has conducted non-lethal surveys in the Antarctic Ocean since exiting that organization in 2019, sponsored by the Japan Fisheries Agency and carried out by the ICR.

Data collected from this year’s survey will be supplied to the IWC’s Scientific Committee, the Ecosystem Monitoring and Management Working Group of the Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), and the Scientific Committee of the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO).

Blue whale biopsy sampling © Institute of Cetacean Research

Oceanographic whale research. © Institute of Cetacean Research

The previous survey reported that multiple species feed in the same waters of the Antarctic, including blue whales, Antarctic minkes, fin whales, and humpbacks. It also stated that the ongoing recovery in the numbers of fin whales and humpbacks is becoming clearer, and that multiple observations of the blue whale ー considered to be extremely scarce ー indicate a recovery in that species as well.

Separately from the scientific surveys, several Japanese whaling ships have since 2019 hunted whales commercially in the country’s territorial waters. Five shore-based small whaling boats, and a factory whaling fleet, have a quota of over 400 whales, including species such as minkes, Bryde’s whales, and Sei whales. In addition, local communities across Japan hunt smaller whales and dolphins closer to shore.

Collected whale skin samples. © Institute of Cetacean Research

Oceanographic whale research vessel the Yushin Maru. © Institute of Cetacean Research

Kyodo Senpaku, the company that operates the factory whaling fleet, announced last year that it would aim to build a new factory ship to begin operations in 2024, retiring the current 8,145-ton Nisshin Maru.

Whale meat is nowhere near as popular as it was in postwar Japan, when it helped feed a hungry nation. It is, however, still readily available in restaurants across the country.

Whale dishes remain a popular part of the local food culture in coastal whaling towns, some of which have a documented history of hunting whales that goes back centuries.

RELATED:

- New Whale Meat on Plates in Taiji as Fishermen Adjust to Whimsical Kuroshio Current

- INTERVIEW | Fishmonger Asana Mori: ‘Whale is Delicious so First, Give it a Try’

- Whaling Nations Should Take A Stand As ‘Activists’ Meddle with Food Culture

(This article is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research in Japan. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.)

Author: Jay Alabaster