Part 1 of 2

In October 2022, the International Whaling Commission will hold a meeting in Slovenia.

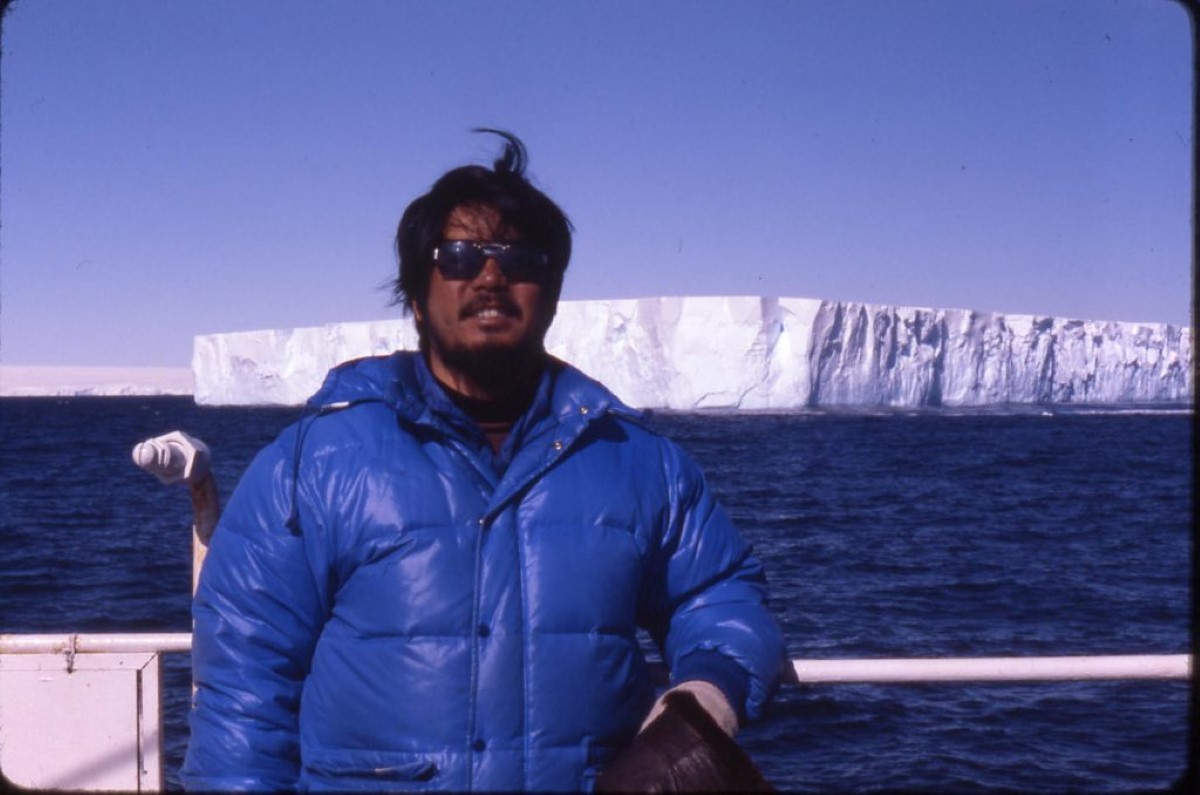

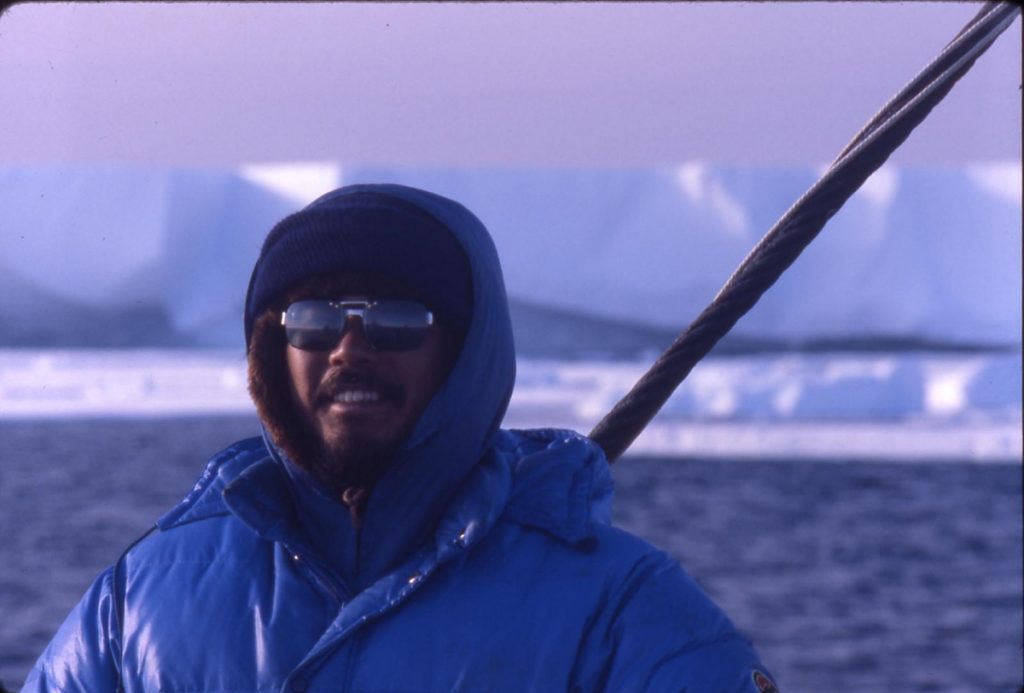

This is the first of two articles based on a conversation with Dr Hidehiro Kato, one of Japan’s top whale researchers, currently Professor Emeritus of the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology (TUMSAT) as well as a Scientific Advisor of the Institute of Cetacean Research. He has been a member of the commission’s Scientific Committee for over four decades and formerly served as cruise leader for the first Japanese research whaling expeditions under a special scientific permit in the 1987/88 austral summer in the Antarctic.

It would probably surprise many in the world today to know that there is an active international organization devoted to “the orderly development of the whaling industry.” It consists of 88 member countries, including staunchly anti-whaling nations such as the United States and Australia, Netherlands, and even landlocked countries like Switzerland and the Czech Republic.

In October 2022, the members of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), which has held regular meetings since its formation in 1946, are due to assemble at a meeting in Slovenia. But Japan, one of the world’s most active proponents of whaling, will attend only as an observer.

Japan famously withdrew from the IWC Convention in 2019, after watching the group turn hostile to any commercial whaling and block all requests for a quota, even for species with proven ample stocks in the wild.

Optimism from a Whale Expert

One of Japan’s most renowned whale biologists, however, remains optimistic for the future. Dr Hidehiro Kato has sailed on research voyages around the globe since 1978, including repeated trips to Antarctica, and served as the scientific cruise leader of Japan’s first research whaling expeditions under the country’s special whaling permit. The well-known scientist has worked extensively with whale specialists from other countries.

As a researcher who has spent over four decades as a member of the IWC’s Scientific Committee, which is composed of the world’s top cetacean experts, he believes that there is still a path to compromise, with sustainable whaling quotas based on solid science.

“In the future, there is the possibility in the mid-term that Japan rejoins the IWC, and once again takes on the challenge. For this reason it’s important to keep collecting scientific data, so that we have a sequence over time. I hope I can contribute to this effort,” Kato said at an interview in Taiji, where he lends his expertise as an honorary member of the local Whale Museum.

From Seals to Whales

Kato learned the importance of international cooperation early in his career, when he was still a graduate student. He was studying ice-inhabiting seals based out of Hokkaido University in Japan’s northern region, working alone and not making much progress. A professor and some senior cetacean scientists suggested he apply to join an IWC international survey, which turned out to be life-changing advice.

“In 1980, I went to Antarctica, with researchers from five other countries,” he said. “This research went on for seven months in total.”

“This may seem like a long time, but I had been struggling working alone on my research on seal surveys in the past, and now I was able to relax and work in a team. I was able to do research that was praised by the others. I decided to change my research theme to whales.”

Kato was hired by the Whales Research Institute in Japan, a predecessor to the current Institute of Cetacean Research, which oversees whale research in order to ensure sustainable stock management. He became a specialist in determining the age of baleen whales using earplugs accumulated in their external auditory meatus (inner ear), which lengthen as they grow. In 1979 he joined the IWC’s Scientific Committee, a post he still holds today.

The International Whaling Commission

When the IWC was formed in 1946, just a year after the end of World War II, it was a rare example of a global institution that aimed to manage a natural resource based on hard scientific data. Building on several ineffective whaling treaties from before the war, the group’s charter dictates that the main commission takes recommendations from the Scientific Committee.

Taking a scientific approach, the Committee in turn conducts and collects research, and now publishes a peer-reviewed journal of research, the Journal of Cetacean Research and Management.

Turning a Moratorium Into a Research Opportunity

In 1982, just after Kato joined the IWC/SC in 1979, the Commission famously enacted a temporary, blanket moratorium on commercial whaling to let stocks recover, which likely saved several key species from extinction. Japan shifted to research whaling, allowed under the Commission’s charter to collect data but highly scrutinized internationally.

“When I started my work with the IWC, it was the very end of the period of commercial whaling,” Kato recalled. “My observation is probably a bit different than other scientists in Japan, but during the moratorium, [in the scientific committee] we worked under a lot of pressure, but it wasn’t a totally bad time.”

A Chance for Firsthand Research in the Wild

Kato had the opportunity to be the scientific cruise leader for Japan’s first research whaling expeditions, which aimed to collect data to prove important biological parameters necessary for successful cetacean stock management, and subsequently lead to sustainable commercial whaling. He saw the shift as a rare opportunity to study the animals in the wild.

“As a scientist who had studied seals and sea lions, and now minke whales, of course I wanted to know more about them. What kind of lives did these animals live? What were they up to? How could we create the best relationship between humans and whales, to foster their sustainable use?”

Scientific Sampling

As a scientist, research whaling provided new opportunities to collect data without any sampling biases, opportunities which hadn’t existed in the era of commercial whaling. As in other countries, up until the moratorium whale researchers had joined commercial whaling expeditions, where naturally profits were a priority.

“Up until then, we conducted research in the context of commercial whaling, which took precedence. So for instance, in commercial whaling, the larger whales tended to be caught, even from the same species, creating a large bias” in the data, he said.

“When Japan began research whaling, we made it free from sampling biases, so that whales were taken using a random sampling process,” he added. “We were under a lot of pressure when we conducted research whaling, but it was a benefit from a research perspective, as a matter of science.”

Gap Between Research and Politics

As a scientist, Kato naturally hoped that the IWC would act based on the results of the scientific research, allowing quotas for species that had demonstrably sufficient numbers in the wild. But whales had become a totem of the environmental movement, and the organization’s decision-making process became highly politicized.

Efforts by pro-whaling countries like Japan and Norway to end the moratorium, even for more stable species, were met with strong resistance by former whaling countries that turned against whaling as well as environmental groups, with activists holding rallies outside of the Commission’s annual meetings.

“Without the anti-whaling movement, I believe that we could have kept whaling. And in that environment, we wouldn’t have failed in managing whale stocks.

“We had safeguards such as research and management. I don’t think whaling countries would have taken too many whales in those conditions, as long as the IWC whale stock management scheme was in place,” Kato said.

Next: INTERVIEW | Hidehiro Kato: Battle for Science, Sustainability over Politics in the IWC

RELATED:

- INTERVIEW | Hirohiko Shimizu: Japan’s Whale Research is Misunderstood, in Fact a Force for Good

- INTERVIEW | Hirohiko Shimizu: Japan’s Whale Research is Misunderstood, in Fact a Force for Good

(This article is published in cooperation with the Institute of Cetacean Research. Let us hear your thoughts in our comments section.)

Author: Jay Alabaster